by Zoe Grace Marquedant

Zoe’s essay appears in episode 32 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

You’re handed a laminated card with a number of it. You’re not necessarily the “18”th person in. The order has been thoroughly scrambled since mid-morning by the light, but constant foot traffic. They’re just not at capacity yet and you are somewhere in that number. You’re offered a pump of hand sanitizer and a basket.

Last week, you bought pasta, canned tomatoes, kidney beans, dry chickpeas that need to soak so you better know hours beforehand that you’ll want falafel later, tea bags, cheap wine, bread, cheese on sale, a bar of dark chocolate to split between the five of you.

Now when moving through the racks of pickles, tomato paste, and mustards, past the open-air fridges and chest freezers, you keep your eyes on needs, try not to think of wants, of saliva, of fat and grease. Try not to look at the plump chips fluffed so they appear to be bursting from their shelves, the sleeves of assorted cookies with chocolate ribbons, wafer layers, jam centers.

Try not to look at the plump chips fluffed so they appear to be bursting from their shelves, the sleeves of assorted cookies with chocolate ribbons, wafer layers, jam centers.

You’re allowed to have some things. Not everything. Alcohol, but no brand cereals. Side dishes with dinner, but no dessert. Not often. You’re budgeting, doing math in front of the eggs. You mentally cut things into servings, divvy it up, and try to guess if it’d feed everyone. And if so, more than once?

You start buying ingredients in relative bulk instead from the agricultural supply place next to the river. It’s closer. Milk and yogurt you get from the shop across from the apartment that’s open late on Thursdays and Fridays. It’s more expensive than the supermarket, but you cut down on travel time. You cut down on outings.

After, you push a few tins to the back of the cabinets. Extras, secrets. For emergencies. Birthdays. You live with two Spring babies. You’re not sure what it would look or feel like to celebrate in the given situation, but you squirrel away a can of peaches, some of the good sugar, and hold on to the idea.

After, you push a few tins to the back of the cabinets. Extras, secrets. For emergencies. Birthdays.

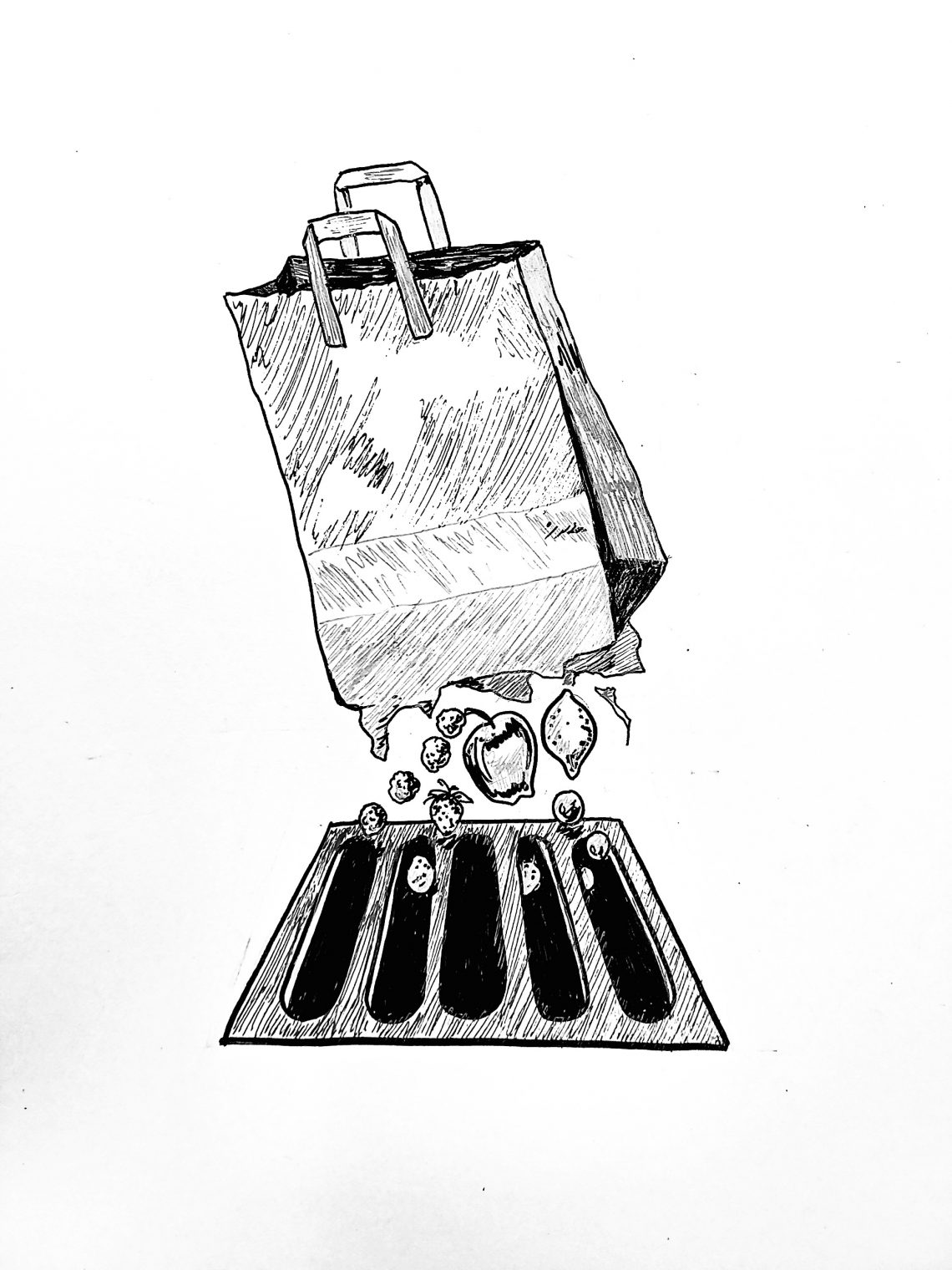

After all the stores have mopped their floors, you head back into town with Leo, leaving the other three at home. He has lights on his bike, goes first. You park near a practically disused kebab shop. Meaning no cameras. You walk. A friend told you where you’d find the truck, backed up, almost flush with the building and full of produce. All bagged and ready to be trashed elsewhere. You don’t know exactly what’s inside. Every time, you keep your hopes simple.

You’d only been inside the store once. It was the kind of place that had an in-house cafe, both a meat and fish counter, banners of smiling farmers, a spare parts and repairs desk, some sort of promise to customers written prominently across one wall in cursive. A type of nice that you can only think about briefly before it becomes exorbitant, annoying, and unattainable. But that also makes what you’re about to do easier.

There’s a plastic shoot as wide as your shoulders that leads to the truck’s bumper. You have to be quiet, travel backpack-first, and know which of three buttons is “open” and not “close” or worse “light.” You fish around with your toes, feeling for footholds, and hoist yourself in. Wide, wheelable bins as tall as your belly button are strapped to the walls. One bin has only empty detergent bottles. Another bin might just be paper. There’s a mailbag. To the back, you can see the sheen and sudden color pop of vegetable skin.

You and Leo take turns sifting through the food, filling your backpacks. Heavy, bruise-resistant items at the bottom. Crushable, spillable, anything that could trickle or burst towards the top. You keep keys, wallet, anything important, anything identifying, anything you could accidentally drop in the small front pocket. You barely debate what to include. There’s little you won’t eat. Little you can afford to leave.

You barely debate what to include. There’s little you won’t eat. Little you can afford to leave.

A Hawaiian pizza, two burratas, miniature roman cauliflower, regular-sized cauliflower, red and yellow bell peppers, endive, lamb’s lettuce, bags of potatoes, ready-made pancakes, rosemary sprigs, croissants with salt and butter, a slightly punctured bag of flour, a container of sundried tomatoes, a mango, an avocado, bananas, finger-sized cucumbers, raspberries, blueberries, king oyster mushrooms, a pear, bags of oranges, quark, something called “Sunday Bread.”

You chance it on a paper tray of Berliners. You don’t even really like donuts, but they look grainy with sugar, and what are the odds of getting food poisoning from something that’s basically deep-fried preservatives? Cheesecake, fish filets, pork chops are birthed from the abyss of bags within bags. You look at each other. They’re tossed back.

Sometimes you get selective, separating the best-of, carefully plucking the putrid, mold-ridden strawberry from within the box. You heft a decent-sized, defendable-looking cabbage with the fewest scratches. Items that can be beautified, peeled back, made over should anyone ask why you got it. You try not to get too excited. Try not to think of too many recipes in case something is soft on the inside. In case what you thought in the light of a headlamp was ok turns out to be profoundly rotten.

You try not to get too excited. Try not to think of too many recipes in case something is soft on the inside.

Mostly it isn’t and you stand confused, turning a basket of grapes over in your hands, trying to decipher why it was discarded. No marks, smells, signs of expiration. No date. You take it and spend the ride home thinking of ways to stretch each ingredient, renew and showcase it, hold everyone’s interest. Again and again. For breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Breads, salads, soups, mashes, sautees, stir-fries, anything that can be served over rice.

An assembly line of washing, cutting, storing, freezing, and arranging forms at the kitchen table. Brown spots, molds, blemishes are pared off. Cellophane is peeled back and balled up next to the sink with the other recycling. You wonder whether or not anyone has ever touched this radicchio with a bare hand, if so…how long since? The compost bin quickly overflows with wilted leaves, stalks, peels, rinds. Soon there’s a bowl of fruit in every room.

After everything is organized, you strip and shower. Not strictly because you sifted through garbage for a half-hour, but because somewhere in one of the bins a yogurt popped and slimed all over everything, including you. You wash the deep earth smell of ruffage off your hands. Check your clothes for stains that might need soaking. Oddly, you don’t feel like you need to be deloused any further. You don’t fear that you missed a spot or spore and now something sinister is breeding in that small patch of skin behind your ear.

Somehow the truck felt clean. No obvious odors, puddles, reasons to think about the permeable nature of fabric and shoe rubber. Something non-threatening about the over-compartmentalized almost scientifically sorted bins.

Somehow the truck felt clean. No obvious odors, puddles, reasons to think about the permeable nature of fabric and shoe rubber. Something non-threatening about the over-compartmentalized almost scientifically sorted bins. The emptiness, the silence. Compared to the flurry of hand wipes when you enter through the front door of any store. This took a fraction of the energy. There was no avoiding people, no calculations, no distances, no mental acrobatics of justifying choices, no guilt. Just the act of carrying.

For the first time maybe all year, the anxiety of time and health and money spends the night in someone else’s body. The morning is in a few hours and when it comes you sit in the sunny all-meals room alone and slowly eat nothing but berries for breakfast.

Original artwork by Claire Winkler

About the Author

Zoe Grace Marquedant (she/her/hers) is a queer writer. She earned her B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and her M.F.A. from Columbia University. Her work has been featured in Olney Magazine, the Cool Rock Repository, and Schuylkill Valley Journal. She is also a columnist and contributor for Talk Vomit. Follow @zoenoumlaut.