By Jonathan Ammons

Jon’s essay, “Nostalgia,” appears in The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, episode 1, which aired May 18, 2018.

Of all the feelings we experience in our pantheon of emotions, nostalgia is surely the most painful to endure, especially the first time. The first time you hear a song from a decade ago and remember that kiss with that girl on that beach, you feel the sting. You will never kiss her again, you will probably never be on that beach again, and you just wish you could feel the exact way you felt then. Naïveté. Lust. Simple ignorance of how precious it all was. The realization that it will never feel that crisp, vibrant, and real again, because from now on, it is no longer an experience, it is merely a memory. Far off and faint, drifting rapidly into the distance. It is the seed of regret. It’s a photo, fading from the sun, and every day it fades a little more.

It’s 2004 and I’m stepping off the tarmac on a tiny Honduran island called Guanaja. It is beautiful. The crippled mountains shrink back from a blindingly bright blue sky, a sparkling ocean ripples just yards away. Clear blue water, clear blue sky. The air is ripe with foreign smells: salt water, sewage, cigarette smoke, smoke from a wood fire. We’ve come back to help our old friend Allen prepare and distribute care packages to his impoverished neighbors. It is the third of my trips to this hurricane-ravaged island and I do not yet realize that it will be my last.

I do not realize, that as I sit on the street corner and pull an empanada out of the brown paper bag, that it will be the last time I taste what has become one of my favorite meals. The crispiness of the dough, the leanness of the island beef, chicken, other mystery meats steamed in the bready pocket, all so brief, and all so perfect. Sitting there on the street corner, I remember the first time I ate them: at a construction site in the town of Mitch, named for the hurricane that destroyed it. My hands had been covered in dirt and debris, and my socks were wet from where a nail had punctured my shoe. A very warm woman with a big, toothless smile approached us with a large plastic bag bulging with piping hot empanadas, feeding the strangers who had volunteered to rebuild her home.

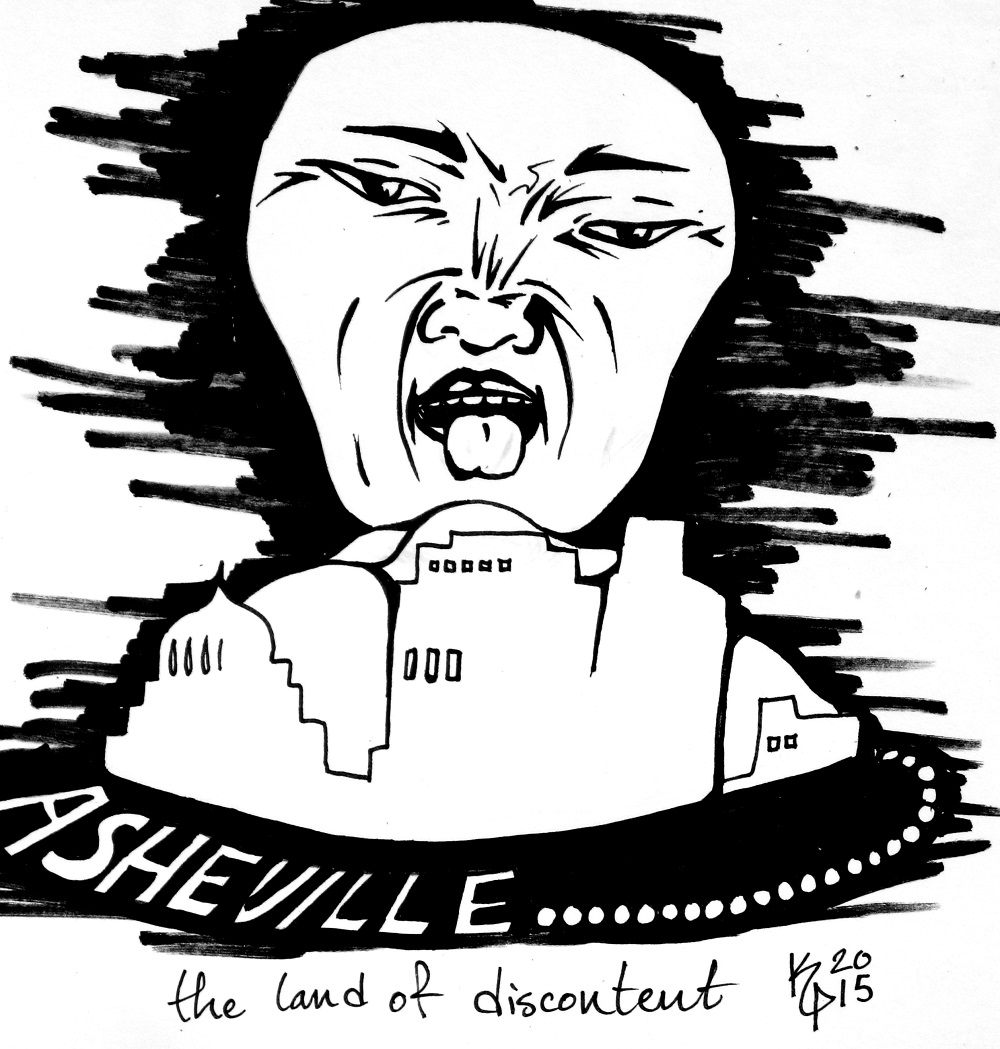

So now, sitting in Cecelia’s Kitchen in Asheville, or Anna’s Empanadas in Raleigh, I feel as though I am missing something. Sure, these empanadas are basically the same thing, but something is severely amiss. And it’s not the pastry, its not the fact that the beef is fattier than the Honduran beef, it’s not even the fact that it’s Jasmine rice.

Sure, these empanadas are basically the same thing, but something is severely amiss.

It is that I don’t hear the pack of stray dogs barking outside, or the kids playing soccer, or the thumping soca beats from the bar up the street. It’s the fact that Allen is not telling me some crazy story about moving sunken boats in the harbor using only an air pump and empty oil drums. It’s that I don’t have mud on my hands and I cannot sit in the shade of some foreign tree and throw scraps to the neighbor’s goat. Instead, I hear modern music. I can smell the sterile cleaning products emanating from this particle board table. My hair waves in the air conditioning.

And suddenly, it’s just not right. None of it.

The other day I was in my kitchen trying to piece together a meal of whatever was left floating around in the fridge. I had just thrown some chicken thighs in the pan, lightly salted and peppered. As they started to sizzle, I caught a whiff of the most familiar and comforting smell. And when I closed my eyes and inhaled, I could picture my late grandmother’s home. I could see the half-wall that divided the living room and kitchen. I could see the long, leaved table and the eight imperial chairs that surrounded it. I could picture the smoke billowing from her oven as she had, yet again, forgotten about the bread and it was now in flames. But most of all, I could picture her: blind, still standing in front of the stove stirring, sipping the broth from the chicken and dumplings.

But most of all, I could picture her: blind, still standing in front of the stove stirring, sipping the broth from the chicken and dumplings.

I could feel the dogs jumping at our legs while we picked at the summer sausage and cheese she always put on the table next to the record player. The TV murmuring in the background. My uncle asleep in the recliner. I could see my mother curled up on the couch reading a magazine, her head wrapped in a shawl, hiding her scars, her shaved head, her thoughts and the fears that drifted through a cancer ravaged brain. As I stood there salivating, sniffing and remembering, I could taste the torn strips of chicken, the soft, supple dumplings, and the gelatinous broth.

My grandmother passed years ago from pancreatic cancer. It graciously took her quickly. And while my mother can cook very well, and though she, now cancer free, still cooks that same recipe for chicken and dumplings, there is a chasm there. And maybe it is just that we are not in that house, or that I am so far removed from that period of my life, but something tastes different. Perhaps it is that my senses have deadened or that my tastes have changed with age, or perhaps my grandmother forgot to tell my mom about a certain ingredient. But I think it is mostly because it is made by different hands and served in a different home. I will never have that meal, that exact meal, again. But I can still taste it.

We cook these foods, we do our best to duplicate them in our own homes.

We cook these foods, we do our best to duplicate them in our own homes. Did she use just a dash of the paprika? Was the heat really this high? I don’t remember using that much celery in the stock last time. We prepare them in our own kitchens, to share with our friends, family, guests, whomever. We have grown, we have learned recipes of our own, but we return to these not out of convenience, but out of conviction. Out of memory, both fond and regretful. Out of a feeling that maybe, just maybe, we can capture those feelings, those comforts, those happier times just one more time. We return to them out of respect.

Jon Ammons is Editor of Dirty Spoon and creator of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

Artwork by Katrin Dohse.