by Jeremy Fredericks

Jeremy’s essay appears in episode 34 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

For the last four years, Ana Garcia has spent her Saturday mornings selling empanadas, soups, quinoa muffins and sorbets at the Old Town Farmers Market in Alexandria, Virginia. From grandparents picking up treats for their grandchildren to a flight attendant who does not like the plane’s food, the customers shopping at Gracia’s booth, Ana’s Twist, love her chicken, ground beef and vegetable empanadas.

Garcia, who created the business in 2017, believes that “empanada means to be shared with your loved ones, with your friends, your family. Since I was little, [my grandmother] taught me how to do empanadas and how to close properly by hand. So that’s why my empanadas are handmade and we don’t use anything to close, just my hand.”

Garcia’s empanadas are just one of many options for hungry customers at the Old Town Farmers’ Market. Taking place in the Market Square since the 18th century, this farmers’ market is the oldest in the country to be held in the same location. Produce grown on former President George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, even made its way to the market.

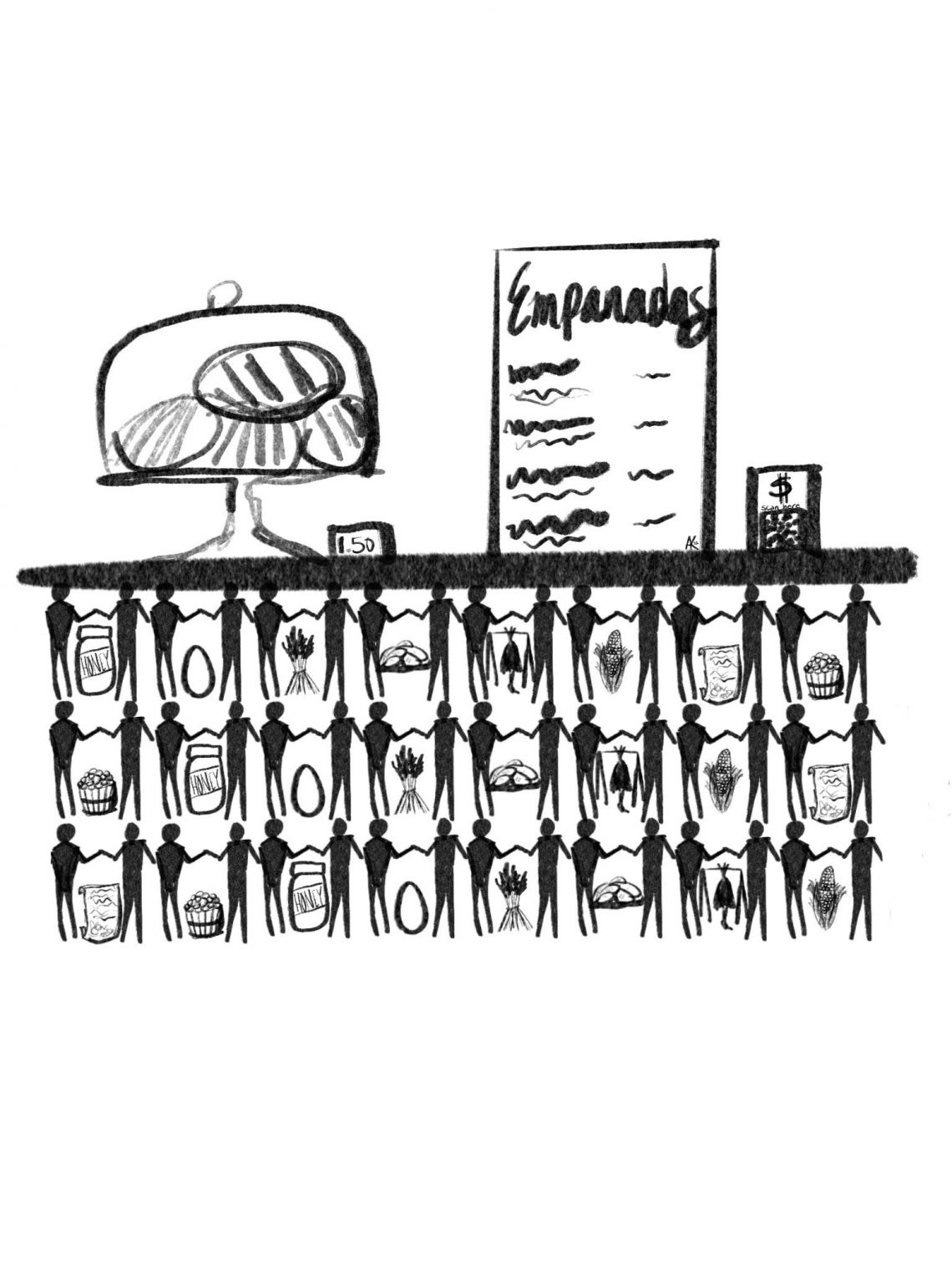

“Washington, as far as we can tell, was not selling at the farmers market,” Sam Murphy, the Manager of Historic Trades at Mount Vernon, said. “But, the slaves at Mount Vernon were selling produce and eggs and chickens at the farm market.”

Enslaved Americans on Mount Vernon received Washington’s rations for food, but were expected to backfill their diets with food they produced. Some decided to sell, not eat, the backfill produce at the market.

“They are having subsistence gardens. They’re keeping chickens and ducks and bees and selling items from those creatures in Alexandria, on Sunday at the farm market,” Murphy said. “Some of the descendants of the Washington slaves, even into the 19th century, were not consuming the eggs being produced by the chickens because they were put up for sale. So what it was allowing the enslaved to actually have income to purchase things themselves.”

One enslaved American who sold at the market was Sambo Anderson. A carpenter at Mount Vernon, Anderson was making a profit by selling honey and waterfowl he hunted.

“We know Washington’s purchasing a lot of honey from Sambo Anderson,” Murphy said, emphasizing the Father of the Nation’s purchases. “The big challenge is…there’s not a whole lot of records. But we do know of instances along the way where they are selling items at the [Old Town] market.”

The Old Town Alexandria Farmers’ Market first began over 260 years ago, according to their website. For about two centuries, it flourished, until just a handful of farmers were selling to customers in the 1970s. By 1989, the number of vendors had rebounded.

David Argento’s father was among those selling at the market in 1989. Argento is the owner of Papa’s Market, a business based out of Orrtanna, Pennsylvania that sells fruits, greens and jars from his farm and partner-farmers in the region. Papa’s has been a vendor at the Old Town market for the last 27 years, beginning with Argento’s father, who thought it was a good business venture. The elder Argento, already a vendor at other markets around Washington, D.C., decided to make the two hour-or-so trip from Orrtanna to Old Town. The younger Argento has followed in his footsteps and realized that the market was about much more than just selling produce; it was about the people.

“It’s one of those markets where you really get to know people very well. And we sort of formed a community around our market. It’s more important than just selling fruit, vegetables; it’s a personal connection,” Argento said. “It’s almost like my second community. I live here in Pennsylvania, but I spend the weekends in Alexandria.”

The market has become the younger Argento’s favorite because of the people that shop there on Saturday mornings.

“It’s certainly my favorite market of all the ones we have,” Argento said. “The history is important, but it’s just such a great community and it’s really deeply supported by the Old Town community. People come to it from other places, but it’s a very important event every week in Old Town and all the residents really feel connected to the market and invested in the market. And we feel mutually the same way, as vendors.”

A typical week for Argento begins with him writing his weekly newsletter, which includes pictures of the Adams County, Pa. landscape, literature and updates on the markets they’re selling at. On Thursday and Friday, he collects the produce at his farm, as well as some grown by a neighbor, and loads it up on his truck to head to Alexandria. After a pit stop delivering produce to partner restaurants in Metro D.C., he heads to stay with a friend in Rockville, Md.

Then, on Saturday, he wakes up by 3:30 a.m. to get to the market within the next hour. After set-up, the market opens at 7 a.m. and for the next five hours, Argento is doing what he loves.

“We have 7 to 12 to enjoy the company of our customers and sell a few things,” Argento said. “From there we have deliveries that we make to customers that, for one reason or another, can’t make it to the market.”

Garcia’s day goes similarly to Argento, minus the deliveries. She became a vendor about six months after applying, which is shorter than most people have to wait, because the manager of the market really liked her empanadas and emphasis on healthy foods. At the market, Garcia was able to venture into her second food-related business.

“We were entrepreneurs in Ecuador. We built an ice cream shop with more than 750 flavors and it was the most popular ice cream shop in Ecuador,” Garcia said. “We moved to [the] U.S. with the same idea to open the ice cream shop with more…so that’s our next step.”

Garcia learned to cook from her mother and grandmother, who is still making empanadas at the age of 103. Ecuadorian traditions, like a soup made of pumpkin, squash, beans and nearly two dozen other ingredients, are a staple at her stand. She is passing on the traditions she has learned to her daughter, now 10 years old, who serves as Ana’s Twist’s taste-tester.

“So I learned from them how to cook. That’s why they really inspire me…so that’s why all my tips are very, very special and that’s what I keep doing here in [the] U.S.,” Garcia said. “My daughter [was] really born in the business…she tries first because kids always tell the truth when it’s something they like or not.”

Continuing on a parent’s culinary lessons is important to both Argento and Garcia. For Garcia, it connects her to her mother, who passed away from a stroke. For Argento, it allows him to be close to his parents, as well as his sister and brother-in-law, who own a nearby farm, orchard and winery.

“When my dad retired from his regular career, he and my mom moved up here to the farm and he started helping Dave [Argento’s brother-in-law] out with farm markets and then it kind of grew into becoming Papa’s Market,” Argento said. “He just got to a point where we couldn’t do it anymore and he hated to quit doing it. So he said ‘well, why don’t you start doing this instead of me?’ So I thought it was a good idea.”

Garcia is now looking for a standalone location, where she can make and sell her empanadas, soups and ice creams.

“We are planning to do that this year, to try to find something just to use ourselves. Then we can have different areas to work because we really won many, many prizes in Ecuador for our ice cream,” Garcia said.

The market is less of a place to sell produce and more of a place to produce relationships. With fewer Americans participating in activities that help them feel like part of a community – like religious services, teams or clubs – the Old Town Farmers’ Market is helping to reverse the course, according to Argento.

“To me, it’s a lot more than just selling food. It’s getting to know people, getting to know their needs,” Argento said. “To the people getting old, we’ll take stuff to their house if they can’t get out. If they’re sick, we’ll take care of them. The biggest thing is just getting to know people, becoming friends. There’s a lot more than just selling stuff.”

And one more thing. For Sambo Anderson, the enslaved man at Mount Vernon, the market served as a way for him to make money and earn his freedom. According to the Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia: “Anderson later used earnings from his hunting operation to purchase and then free several of his enslaved family members, including his daughter Charity; his grandchildren William and Eliza; and Eliza’s children James, William, and John.”

Original artwork by Alex Knighten

About the Author

About the Author

Jeremy Fredricks is a freelance writer based out of the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. He’s written about COVID-19, the 2020 election, and profiles of restaurants