by Morgan Steele Dykeman

“Picking Crabs” appears in season 2, episode 12 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, which originally aired on July 5, 2019.

The foodie within me is thrilled to have a vast variety of seafood at my fingertips here in the Puget Sound region. There are several species of oyster and clam that are totally unique to these salty waters that connect Seattle and Vancouver to the Pacific. Literal boatloads of fish fresh from the waters off Alaska arrive daily, and we have our pick of the freshest, largest crabs in the Western hemisphere.

Seafood and saltwater culture are woven into the identity of this place. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to live here.

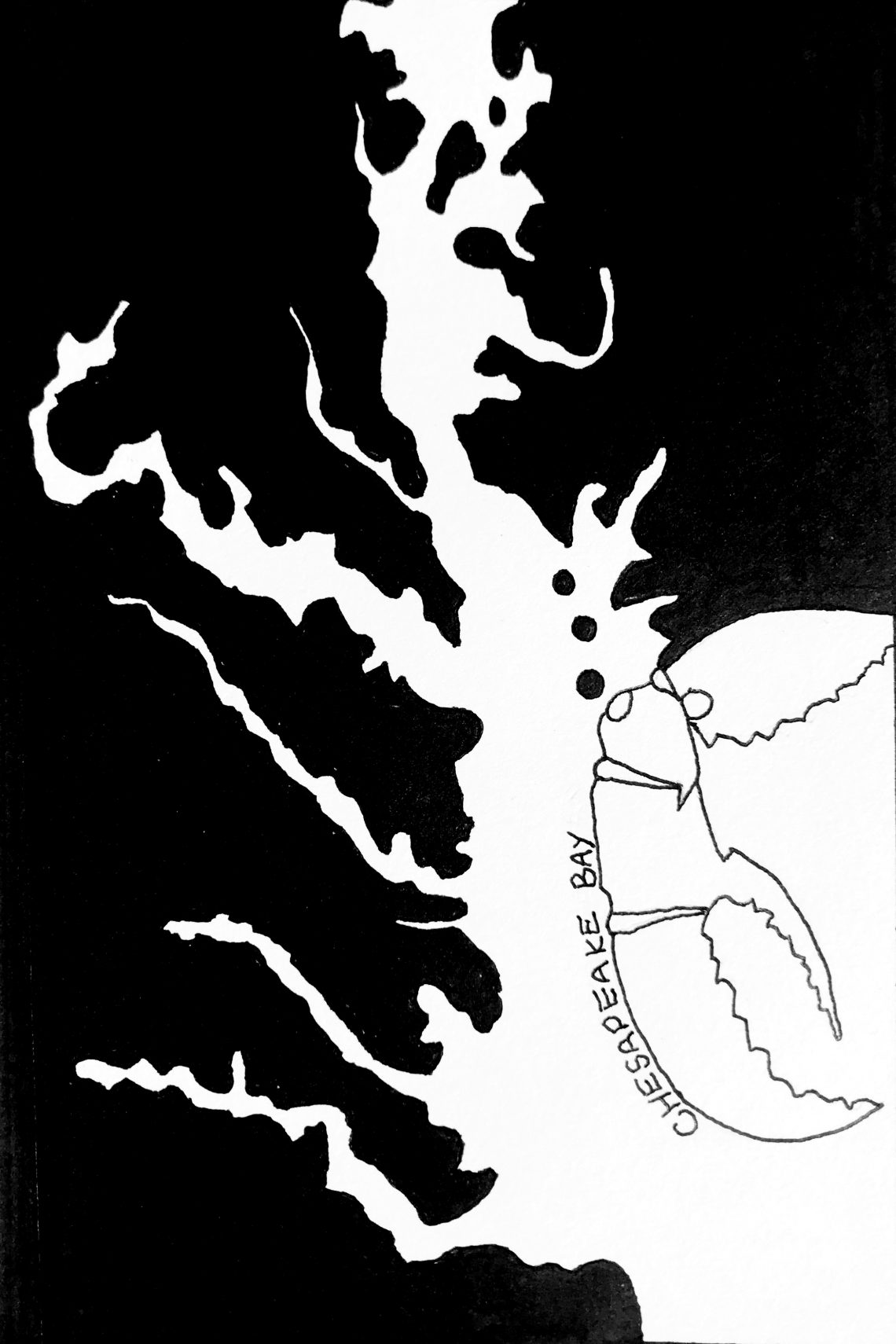

I’m from Maryland, which has a special connection to the water, too. I grew up as a self-proclaimed river rat, spending my days April through September swimming in the Severn River, a brackish tributary to the Chesapeake Bay.

In spite of the plethora of sea creatures I could eat here on any given day, Maryland blue crabs are still my favorite crabs. Florida can keep its Stone Crabs and Maine its Lobster, Alaska’s King Crab and the bayou its crayfish. They can keep the butter and fancy claw crunchers and little plastic bibs.

All I want is a hot, steaming pile of blue crabs smothered with so much Old Bay it makes your eyes water.

All I want is a hot, steaming pile of blue crabs smothered with so much Old Bay it makes your eyes water.

Sure, the sweet tasting snow crab is the easiest to pick and the most bang for your buck in terms of meat output for effort input. The King Crab is the most flavorful and has a pleasant density to its texture. Here in Washington, the salty Dungeness crab is considered our local crab, one which you pick apart most similarly to the way we pick blue crabs. I like all those crabs, but to me they don’t hold a candle to blue crabs, which other folks have a hard time understanding.

I get it. Blue crabs are small. Their shells are sharp and tough to crack. You have to really get in there and dig out the meat — with your fingers, not a tiny fork or knife. The meat doesn’t even taste particularly good on its own, which is why we dunk the clumps of meat in white vinegar and then coat them in Old Bay.

A few weeks ago, I went out to happy hour with a rich techie friend and he started rambling on about the best Dungeness crab he ever had at a pricey downtown restaurant that charges by the claw. He asked me what my favorite crab is. I felt a little embarrassed and a little protective over my puny blue crab roots. He made a confused facial expression when I gave him my answer. I’m not surprised. A lot of folks out here have never even heard of Old Bay, much less blue crabs. He told me that where he’s from in Connecticut, they throw those crabs back or use them as bait. A spurt of resentment boiled up within me as I listened to him trash my favorite childhood treat.

When I went crabbing with my dad during my childhood, I felt pure joy. My dad would wake me before the crack of dawn and we’d walk silently through the neighborhood to the riverside. I remember the worn, cool grey-brown wood of the dock, the soft rhythm of the waves lapping against the hulls of boats moored in the shallows, the way we whispered to each other because we didn’t want to disturb the calm of the early morning.

Catching crabs, like eating them, was a time-honored tradition in my hometown passed down through generations. I loved the way my dad would stroke his chin while scoping out the pilings for crabs, the clumsy way he’d fasten twine to the butt end of a board with his chewed up fingernails, the way he used our kitchen scissors to snip the chicken giblets up into bite-sized chunks for use as bait.

Catching crabs, like eating them, was a time-honored tradition in my hometown passed down through generations.

I loved laying belly-down on the dock with dad, looking down into the muddy brown water, waiting to see if the twine would become taut — a sure sign that a crab was on the line. Dad would slowly draw in the twine with his fingertips, inch by inch, and when the crab became visible I’d scoop it up with the net.

My happy hour friend probably never caught a crab himself in his life.

The crab he paid $20 for was probably hauled up out of the Bering Sea by some poor boy risking his life for minimum wage up.

Over our drinks, my friend moved on to describing the class and grandeur of the restaurant. I imagine him eating a crab off a china plate with a silver fork, cloth napkin tucked into his shirt collar, chasing it down with fine wine. It all seemed so wrong.

In Maryland growing up, when dad and I brought home a bushel of crabs, the whole family knew we were in for a treat. A Maryland crab feast is an all day activity. There’s the catching of the crabs, the cooking and preparation of the crabs, the waiting for the crabs, and the eating of the crabs. With most other kinds of meals, the eating may take only a fraction of time that the preparation does. Not so with Maryland blue crabs. This feast in Maryland takes hours, and often more.

After catching the crabs, you have to start preparing the food. Dad would yank our crab pot out of the bottom cabinet and stick the towering silver artifice atop the grill on the back porch. A crab pot is something every Maryland family has, even if they only use it once or twice a year. You add water to the pot until it’s a few inches deep, dump your live crabs in, and then steam them. Dad would mind the crab pot with a Bud Light in hand while my mom, sisters and I prepared the table. Maryland crabs are messy, and that’s part of what makes them fun and delicious. We’d grab a few copies of the Baltimore Sun and unfold them, layering them across the kitchen table which we dragged outside onto the porch, so that the table wouldn’t get too dirty. Mom would hand me a roll of masking tape and together we fasted the newspaper to the table. Then, she pulled the supplies out of the cabinet: wooden mallets, butter knives, ample canisters of Old Bay seasoning, small cups of white vinegar, a bucket for beer and a bucket for scraps, and several rolls of paper towels.

A crab pot is something every Maryland family has, even if they only use it once or twice a year.

Even I can admit that the downside of Maryland blue crabs is that you don’t get a lot of meat out of a single crab. So, to fill our bellies, Mom always steamed some Maryland white corn and potatoes, which were also dumped into buckets on the table. When the crabs were finally done steaming, Dad dumped them on a cookie sheet and Mom slathered them with Old Bay. We kids licked our lips and eyed the crabs, which were blue when we caught them but became bright red once steamed. When the parents sat the mountain of crabs down on the table, we dove in.

Picking crabs requires a special dedication and patience. Each family has its own preferred method that gets passed down from one generation to the next.

It’s a gruesome process: snapping legs off at the joints, cracking the shell open by hand and scooping out the guts. Maryland Blue Crabs have small spikes on their shells, and no one leaves the table unscathed — everyone gets a few cuts on your fingers, the sting of which is made worse when the Old Bay gets into them.

Eating just one crab can take up to 30 minutes because you have to pick all the meat out of the nooks and crannies, yielding about a quarter cup of meat if you’re lucky. The meat alone doesn’t taste super great and can often taste fishy or salty, but you dunk it in vinegar and coat it in Old Bay. There’s no butter, no gourmet remoulade sauce, no bibs or silver tools for cracking claws. In Maryland there are no tiny forks, either. No forks of any kind, actually, and no plates either. This is the common man’s feast: a meal anyone within walking distance to a river could catch and prepare for themselves.

This is the common man’s feast: a meal anyone within walking distance to a river could catch and prepare for themselves.

There’s no glory in blue crabs, no finery or niceness. As far as food goes, blue crabs don’t have lots to offer, but it’s not the food itself that gives blue crabs their value: it’s the community, the practice, the cultural norms around catching and eating them.

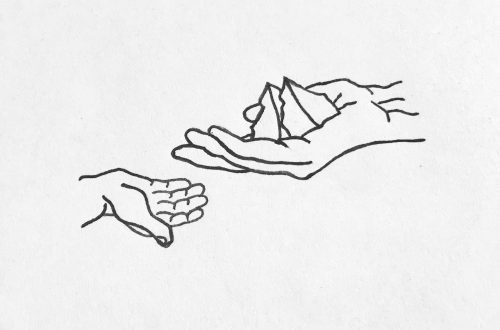

So, even though we have all the seafood we could want out here in Seattle, when I got engaged a few years ago my dad still ordered a bushel of blue crabs to be delivered by airmail from Maryland for my engagement party. We had to hunt down some wooden mallets and use the Seattle Times instead of the Baltimore Sun for our tablecloth. I got to teach my younger cousins how to pick crabs and passed the practice down to the next generation.

Original artwork by Corinne Pease.

About Morgan Steele Dykeman

Morgan Steele Dykeman wields strength in vulnerability and an irreverent sense of humor to craft personal essays about feminism, relationships, eating disorder recovery, and life in the Pacific Northwest. She lives near Bellingham, WA with her car-enthusiast husband, senior citizen doggo, and three dozen house plants. She’s a tenacious advocate for social justice, a committed community organizer, and an irrepressible optimist. By day, she manages the legislative affairs program for NARAL Pro-Choice Washington, and serves on the volunteer board of a local grassroots group called the Riveters Collective. When she’s not rallying or writing, you can find her buying more houseplants, to her husband’s great dismay. Read more at: https://www.morgantic.com/