by Meredith Leigh

This excerpt from the introduction to the forthcoming second edition of The Ethical Meat Handbook appears in Season 2, episode 12 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, which originally aired on July 5, 2019.

As I put the finishing touches on the second edition of this book, the sun is coming up, and the quality of its first light is pulling my eyes eastward over the ocean, away from the computer screen, as if by some great magnet.

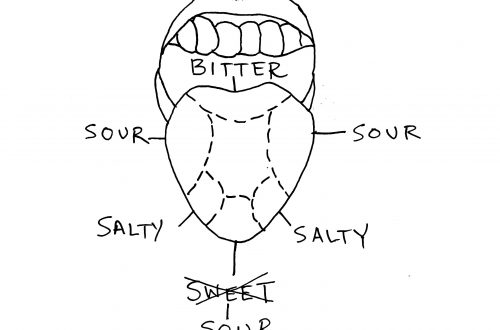

I go outside and put my bare feet on the ground and let it wake me. As this is happening, leaves the earth over are opening, and the instantaneous increase in temperature, which does not seem appreciable to my partner, who is fishing in the surf and shivering, is enough to wake up more microorganisms than there are grains of sand in the entire world, and they begin to breathe and eat and release and die in a dizzying infinite orgy of heat and sugar and acid and gas, thereby (among other things) producing the smell I associate with a spring morning. I marvel, for this ritual sun gazing feels novel to me, yet is as ancient a human practice as our oldest civilizations, and pre-dates even human animals, in a contract between the sun and non-human existence that traces to a blindingly improbable moment, when the chemical trappings of our planet crashed with the sun’s energy to produce what we now often take for granted: life.

The sun’s light has not yet reached Redwood City, California, where the company Impossible Burger is headquartered. I have recently read about their process to produce the bleeding plant-based burger that is all over menus and the media, made from soy and potato and a liquid ferment of genetically modified yeast. I have not seen their production facilities, or the vats of liquid heme protein within them, but I can imagine its color.

Just days ago, I uprooted my garden cover crop of oats and Austrian winter peas, and raked through soil the color of dark chocolate to look at the tiny nodules on the roots of the pea plants where Rhizobia live. Rhizobia is a type of bacteria that can take nitrogen from the air and convert it to usable form for plants. “Nitrogen fixation” as we call it, occurs in these nodules, and if I dust the soil from them and my hands, and gently pierce the nodule with my fingernail, I can see a blood-red or pink color to assure me that the relationship between these peas and their Rhizobia herds has been successful. This color is produced by leghemeglobin, which is the same protein that Impossible Foods uses to make plant based meat bleed and taste meaty.

The process of nitrogen fixation in the nodules of legume plants, such as my garden’s pea cover crop, depends on the health of various biological pathways, and involves the enzyme nitrogenase, which contains iron, cobalt, and/or molybdenum— mineral components of soils in right balance.

Recently, I have been studying the epigenetic regulation of mineral deficiency in plants as well as in humans, which is to say the systemic response to environmental conditions that is remembered by plant and animal DNA. Did my garden soil contain enough cobalt or molybdenum to enable nitrogenase catalysts for Rhizobia to do its work? Had it not, the nodules on the roots of the pea cover crop may have been merely white or a pale banana color, but the plants would grow all the same, and I might pick their shoots for a salad, and go about my day. But what signals would the lack of trace metals send to the pea plant as it grew, and produced seed for next year, and even to my body, or the bodies of my offspring, as I ate a salad from my garden? Impossible Burger uses genetic technology to isolate leghemeglobin from soybean root nodule bacteria, and then encodes it into yeast which, when fermented, multiply and produce more leghemeglobin, which churns in stainless steel vats, ready to be added to the company product.

I pull the roots and the shoots of my oat and pea cover crop aside, and make tracks in the deep coffee-colored soil for my onions, cabbage, sculpit, kale, and leek crops.

A proponent of low till agriculture, what I am doing slightly disturbs me, just as it disturbs the hyphae of many beneficial soil fungi, such as mycorrhizae, which I have spent a year or more ensuring a home in my garden. The Barefoot Farmer Jeff Poppen swears by a minimal, shallow disturbance of soil at seasonal transitions, to kill the microbial communities associated with one seasonal crop, and an awakening and fermentation of the new generation of soil life. On the basis of this belief, he grows 8 acres plus of organic vegetables without irrigation, every single year. I solace myself with this thought, and I watch a dazzling exodus of earthworms as it makes its way towards darkness after I’ve disturbed the peace.

The smell, the activity, the solar energy, fermentation, life and death that I could literally feel emanating from my garden at that moment, and on top of it the crashing of the ocean waves and the jiggling, living sea foam on the beach today, gives me muse for a thousand years of Impossible Burgers. I want food with the sun in it. I want living food.

I want food with the sun in it. I want living food.

There will be a thousand and one attempts to secure food in our day and age.

These include test tubes, pills, and super crops, and we very likely won’t be able to stop the scientific approaches which take nature out of context, so to speak. I don’t deny Impossible Burger its place, and indeed won’t deny its intention, in a colossal and very flawed system.

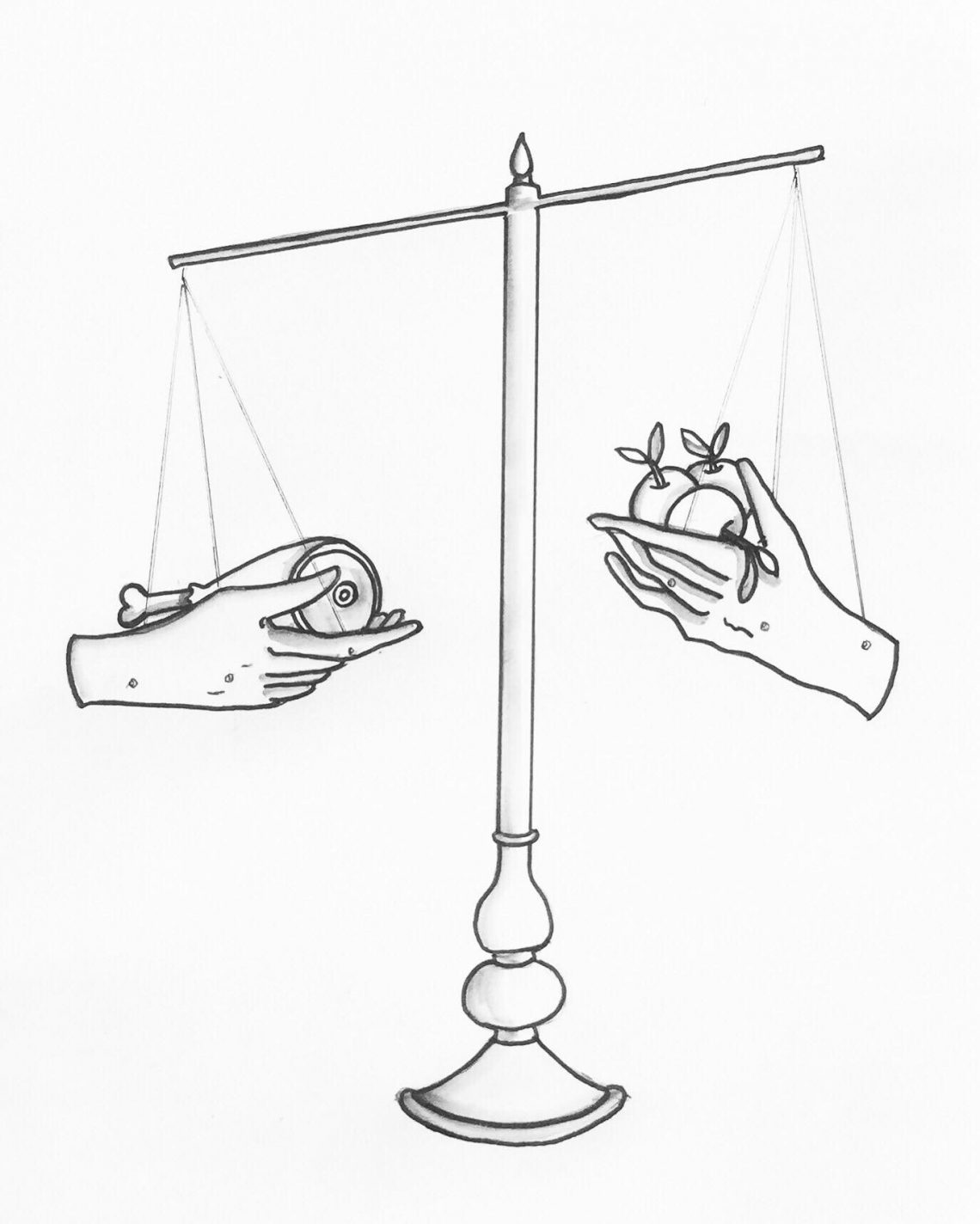

But I am a lifelong pilgrim for food which feeds us more than substance, and food that remains our way of participating in an energetic discourse and a reciprocity with the earth. By this I mean food from the soil, well-raised, full of solar and magnetic and mineral richness, synergy which isn’t being piped to a seedling or encoded in a virus.

There are resonating questions which have heckled me, appropriately, during the revision of this book. They remain: Is it relevant? Is it possible? Are we running out of time?

—

In middle spring, around Mother’s Day, the grass on a North Carolina pasture rises out of incessant rain, suddenly, to waist high. As you walk through it, you can’t help but hold your arms out like wings, letting the seed heads, gravid with risk, brush on the new calluses of your palms. The sheep will be covered over with it, and their lambs down in the depths of the grass will bleat a high, worried song, just so their mothers will answer. The cows with their awkward horns will be up to their chins in food. On the edges of the pasture giant tractors will mow paths beside the road, and cars will swerve off the pavement to make way for broom, poison ivy, privet, multifloral rose, and a litany of other plants eager to make use of disturbed ground. The sheep will peer over the fence I’ve made to sniff at them, nibbling carefully. The lambs will call. The cows will upend their slow tails to swat at flies in the sun.

The sheep will peer over the fence I’ve made to sniff at them, nibbling carefully. The lambs will call. The cows will upend their slow tails to swat at flies in the sun.

This grass, this food, with its constituent cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin is the most abundant food source in the world.

Together with trees, grasses spread over more of the earth’s surface than any other food source. If you stand or sit in the tall grass in North Carolina in May, while the wind blows it like water and the muted purples and grays and greens of the seeds shimmer in the sun, you will wish you could eat this food, and receive of its warmth and its wholesome smell.

But you can’t.

And you will wonder: what if we poison all the honeybees? You might have just passed over a stand of milkweed, and scoured it over to find no Monarch caterpillars. So, what if we mine all the topsoil, collapsing it into rivers and wind? What if we drain all the aquifers? What if we starve out the cobalt, and Rhizobia in their little root houses? What will grow then? What will eat the sun’s gifts, what will root in and send messages to the worms and the protists?

Grass. Broom. Poison ivy. Kudzu. Sedge. Privet. Autumn Olive…cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. And the hooves and the spit, the dung and the piss of the animals who eat that food will be the only thing that can bring back any lively conversation. Any discourse with the elements, with the beetles. With us.

As agriculture remains highly politicized, corporatist and extractive, we need the herbivores.

As agriculture remains highly politicized, corporatist and extractive, we need the herbivores. We need a stewardship of the land that includes animals, and we need the nutrients that they can translate from the sun and the soil and the rain. And if we can put men on the moon, we can manage our relationship with animals mindfully, on any scale.

I choose food with the sun in it. I choose living food.

And so, the intention for this book is the same as it ever was: to heal.

When I wrote it, I was healing myself from a massive fissure in life and in endeavor, and I was simultaneously bringing about a relatively short however storied amount of perspective on healing land and systems for food.

I am astonished at how much I have learned, and how much my positions and understandings have become more complex since the first release of this work. So much has changed, but the seed and the medium have not. We still need, we will need, volumes of thought and practice about the noble contract between people and food that don’t abandon all hope for a positive human relationship with sunlight and rain and soil. This book is based on the belief that on a warming planet, divided by injustice and doubt and starvation on many levels, every eater has a way to conjure hope and empowerment, not tomorrow, but now.

In this update, I hope you will find some of the same information honed, and also new information and thought that speaks to some of the real idiosyncrasies of being an omnivore, in health, in our current times. You will also find deeply considered problems, as ever— my intention has never been to present the equation solved.

I hope you will see, also, what a fantastic dilemma this sort of book is, as it tries to approach the world as it is while fashioning it forward, toward the future.

I hope you will see, also, what a fantastic dilemma this sort of book is, as it tries to approach the world as it is while fashioning it forward, toward the future. My hope is that the conversation continues, and that you take from this work not only meaning and cause to participate in a very worthy exploration of your humanity, but also enjoyment. Community. Vitality. Deliciousness. If we cannot keep sight of those enlivening characteristics, even as we air all of the difficult questions, then we deny ourselves the very thing that will give us longevity: recognition of ourselves as natural beings, as animals, connected participants in a wild yet elegant universe. May we recognize that the privilege is greater than or equal to the challenge ahead.

original art by Maryanne Pappano.

About Meredith Leigh

Over the past 17 years, Meredith has worked as a farmer, butcher, chef, teacher, non-profit executive director, and writer, all in pursuit of good food. She is the author of The Ethical Meat Handbook: A Complete Guide to Home Butchery, Charcuterie, and Cooking for the Conscious Omnivore, (3rd place, MFK Fisher Award 2015) and Pure Charcuterie: The Craft & Poetry of Curing Meats at Home. Meredith works part time for Living Web Farms, and she travels extensively teaching charcuterie and food production and processing. She also pursues other writing, namely poetry and nonfiction focused on the intersection of land and people, and land and the culinary sphere, with work featured in Crop Stories, various Edible publications, and Mother Earth News Magazine, among others. She lives with her partner and four children in Asheville, NC. Learn more at http://www.mereleighfood.com/.