by Jessie Shires

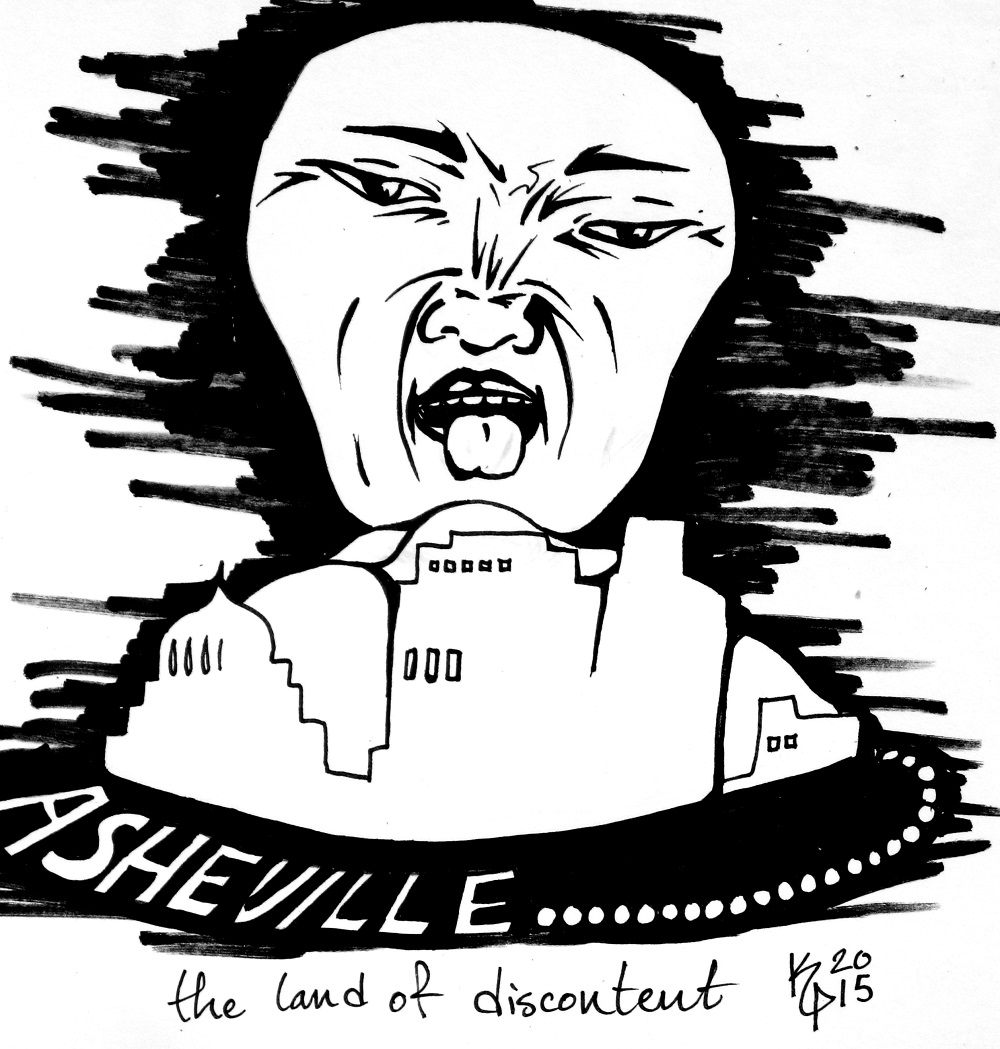

Art by Corinne Pease

Jessie’s essay, “Security System,” appeared on The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour in episode 5, which originally aired on September 7, 2018.

I have cast-iron insecurity.

I should clarify: I don’t mean that my insecurity can be classified as unassailably robust (although that is also true from time to time). What I mean is that I am chronically insecure about my ability to properly use cast iron.

Look around. Blogs the interwebs over will tell you that cast iron is the Cadillac of the cooktop,as essential as a good knife, as classic as beurre blanc. Once properly seasoned, they say, cast iron is better than nonstick. Everything that touches its black satin surface glissades right off, like Olympic ice skaters. Sugars, proteins, fats—any molecule you might ever think to sear or sauté rides a thin cushion of hot oil and virtue around the pan, little smirking hovercrafts that prove your skill and worth as a cook and as a human being. Wipe it out with a bit of paper towel, and peer into its inky depths to take the measure of your soul.

It begins to feel like some sort of bizarre test, with vague but dire consequences for failure. If food sticks to that nonstick-if-you’re-doing-it-right surface, what happens? Revocation of kitchen privileges? Public rebuke in the back pages of Saveur? The ghosts of Julia Child and James Beard materialize, looks of curdling disappointment on their spectral faces?

The stakes feel high.

But what happens if you can’t find the on-ramp for that food-never-sticks, just-wipe-it-out-because-food-never-sticks cycle? So when I find myself scraping away at a layer of egg, or the gooey resin left after prying up the last bits of sausage, is it odd that I take it all personally? I’ll be honest: I’ve cried a few times over a pan, the tears stinging all the more because I remember the moments of triumph when my eggs practically slithered out of the pan of their own accord, so silky and perfect and pinterest-worthy was my pan.

It’s likely that I’m still just getting the hang of temperature on my rented house’s cranky old stove. It’s not reasonable to compare my cast iron, with its mere years of seasoning, to my mother’s, black and shiny as volcanic glass after decades of use. It’s logical to acknowledge that my clearance-priced pans are not in the same league as the two-hundred-dollar works of art I see written up in magazines, handmade by a mustachioed man with tattoos and a leather apron, flanked by a grinning cattle dog, craft beer in hand.

There are many perfectly sound reasons for not yet having mastered this particular skill. And yet… here I am, weeping into my hash browns.

Incompetence is one of my deeper fears. Being incapable. So it’s perhaps no surprise that I admire, desire, and covet useful things.

Incompetence is one of my deeper fears. Being incapable. So it’s perhaps no surprise that I admire, desire, and covet useful things. It’s part of a larger bent: if we all have a fetish, then mine is good design—utilitarianism in the most aspirational sense of the word. If it’s useful, or if it makes me feel more organized, capable, or prepared, I want it.

In a conversation recently, my partner and I were trying to tease out the differences between the artist and the craftsperson. The Venn diagram on that one very quickly starts to look like a pileup at the hula hoop factory, but this distinction seems clear: craft is to be used; art, to be admired.

A chair I can’t sit in, no matter how beautiful, isn’t likely to have a place in my home. Perhaps that’s why I’m drawn to materials like wood and iron and stone. They show use, and by virtue of their durability, they invite it. The handles of my grandfather’s tools are worn dark and smooth at the grip from use by three generations of hands. The granite risers in an old staircase bear smooth, undulating witness to centuries of footsteps, their once-sharp corners softened.

The steel metro shelving in my kitchen doesn’t sag under the weight of crockery like the flimsy pressed fiberboard shelves inside the cabinets do. Durable materials proclaim their capability, defy disposability.

Handmade objects might be the purest expression of my fetish. Things made by hand bear the marks of competence and utility and skill by virtue of their very existence. They beg to be used, because they are already so marked by the touch of human hands. The joints in an heirloom cabinet, perfectly matched and still solid decades after the first kiss of chisel against wood. The fine stitching in a quilt, uniform but not machine-perfect. My favorite coffee cup, from the wheel of an old potter friend, its opening slightly more oval than round. These things bear silent testament to the hours of labor that went into their creation, and to the countless hours of learning and practice and mistakes and progress before the making.

They beg to be used, because they are already so marked by the touch of human hands.

And since mishap naturally arises out of use, the question of repair is another, somewhat hidden consideration of design and utility. If you’re on social media, you’re no doubt aware of kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with seams of gold or other precious metals, and a popular meme of late. The idea of the beautiful scar is poetic, to be sure, but it’s the return to service that excites me. A shiny vein of gold is lovely; but more than mere

ornamentation, it reminds me of the expertise that gave me back the use of my favorite soup bowl.

Knowing how to repair a thing well involves knowing a bit about how it was made, how its materials behave, and how future stresses might reverberate through its restored mass. Repair, and recovery, when done well, are demonstrations of competence. If there’s an altar at which I worship, it’s that. Proficiency, capability, prowess—these are a few of my favorite things.

One of the more intimidating skills I’ve learned, and, in turn, taught to dozens of others, is how to start an IV. My EMT and Paramedic students had already gotten over an important hump when they learned fingersticks and intramuscular injections. It’s no small thing, to intentionally inflict pain, to breach the soft, nervy covering of the body, to access its flowing blood even in this small way. A single bead of bright red wicking into a glucose test strip comes after you’ve taken a stranger’s hand in yours and pierced flesh, brought pain, left a wound. IVs up the stakes. If I’m reaching for that catheter in the first place, you’re sick enough to need it. Maybe very sick. Maybe you’re out of your mind with pain or psychosis, and you flail even as I bring the hollow point to your skin. Maybe you’re a child, and you don’t understand why this person you’ve never met is causing you pain. It’s not a moment for mistakes.

And so when the needle skims the vein, doesn’t gain purchase, slides off to the side, finds no joy, we’ve gone from doing to fixing . And these, my friend, are two rather different tasks.

It’s a skill that crops up in so many places: rescuing a broken mayonnaise, recovering a dropped stitch in a knitting project, navigating back from a missed turn. And it’s more than just a mechanical act: some of the more satisfying experiences I’ve had as a server or bartender have come from the alchemy of service recovery—using every tool at my disposal to transform a guest’s dissatisfaction to delight. Fixing a thing that’s broken—particularly if you were the one to do the breaking in the first place—is a powerful act, and inside it are more than a few life lessons. Keeping your cool, doing what needs to be done from inside the fog of insecurity and cortisol that blows in on the wind behind a mistake, can sometimes be the hardest part. And any deficit in your knowledge base is unmasked, any shortcuts you’ve taken are revealed—I’d argue that it takes more skill to fix the mistake than it does to nail it in the first place, so you’ve gotta be on your game. It’s the unspoken extension of the old saw about having to know the

rules before you can break the rules. Improvisation—and what is an on-the-fly repair if not improvisation?—is most successful when it has a deep back catalogue of knowledge, technique, and, yes, past mistakes and fixes, to draw from.

Fixing a thing that’s broken—particularly if you were the one to do the breaking in the first place—is a powerful act, and inside it are more than a few life lessons.

Which brings us back around to those damn pans.

I’m getting better at it—both the nonstick cooking and the self-recrimination. Things still stick, and it’s best that I expect they always will, at least occasionally. But there’s no more teary-eyed scraping away at the spiteful gunk that just won’t come up. I enjoy the food I’ve made, and later, I scour the still-warm pan with kosher salt and the residual oil, using my fingers so I can feel the particles release from the pan’s surface. It’s strangely thrilling, a whispering echo of the surge that comes with fixing a fuckup. It may be my imagination, but I think things are sticking less frequently now that I have such a satisfying fix. Maybe I’ve just relaxed a little at the stove, knowing that there’s a reliable solution if things don’t go well. If insecurity is the inevitable bedfellow of mistakes, then my personal security system must be an ever-growing repair kit. A repository of tools and techniques; past mistakes and the lessons learned; sticky pans, missed IVs, all those glimmering broken places.

Artwork by Corinne Pease.

Jessie Shires grew up in Craig County Virginia where she lived with her mother in a two room farmhouse with no plumbing and no heat. Weaving her way from Kentucky, to New Mexico, and finally to Asheville, Jessie worked as a paramedic for 7 years spending the last few years of that time doing critical care transport for Mission Hospital. When the helicopter couldn’t get to the person, she was the first responder that found a way. Having left the EMS world behind due to what she calls the “laughably low pay” in North Carolina, she found her way back into the service industry, where she currently bartends at Sovereign Remedies.