by Carol Ungar

Carol’s writing appears in episode 36 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

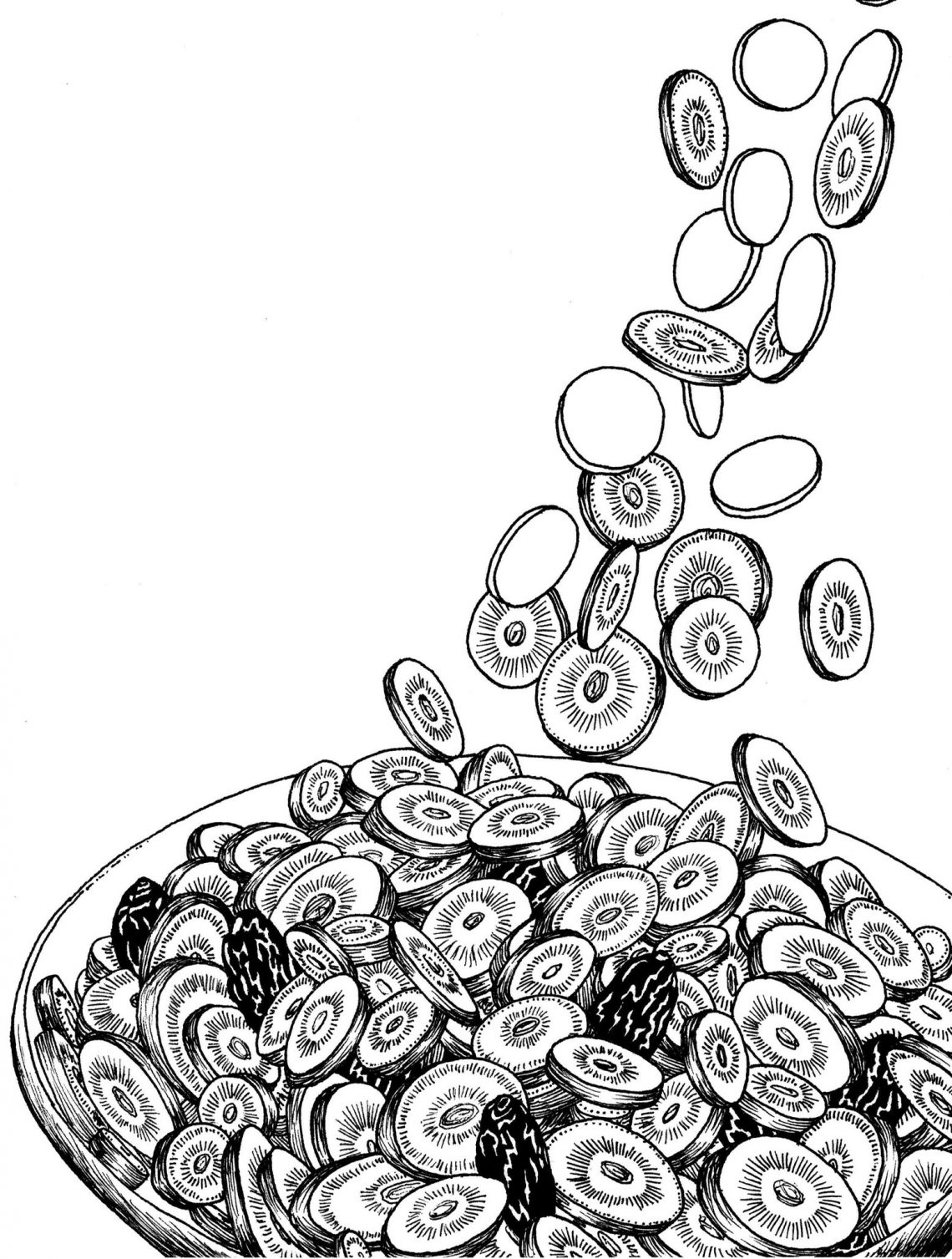

It’s hours to Rosh Hashana and I’m doing what my mother used to do—peeling carrots, slicing them, and braising them in honey. I’m making tzimmes.

It’s odd that I’ve clung to this dish. As a kid I never liked it. My mother, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor had tastier offerings– stuffed cabbage, nut tortes, palachinta,, Hungarian crepes stuffed with ground walnuts and raspberry jam, anything but this.

Then in my mid-twenties, I spent the Jewish New Year with a religious family in Jerusalem. Their table overflowed with agrarian oddities: gourds and leeks, beet greens, and black-eyed peas, even the head of a sheep. I had never seen anything like it before but for me, the biggest surprise was a tiny dish at the end of the table containing what looked like my mother’s tzimmes.

Is that tzimmes? I asked.

Yes, it was.

We didn’t just eat it. We preceded our eating with a prayer, based on a charming wordplay linking the Hebrew word for carrot, gezer to the Hebrew word gezeira, meaning evil decree. The prayer was a request for heavenly protection from evil decrees.

At that point I thought of my mother who arrivedinAuschwitz so late in the war that the Nazis didn’t tattoo her—why waste the ink on someone who would soon be dead? And yet she walked out alive.

But that wasn’t all. My host went on to explain that in Yiddish carrots are called mehren, which means increase. Tzimmes made of carrots intentionally sliced to look like coins is an omen for prosperity. Again I thought of my mother the penniless immigrant operating a successful family business in the heart of Manhattan.

No wonder she clung to the tzimmes. And I do too.

This story reminds me of the Ba’al Shem Tov. For years he visited a spot in the forest where he lit a fire, recited a prayer, and begged G-d to save the Jews. After he died the Jews approached his grandson who was now their Rebbe. “I can’t find the place in the forest, I can’t light the fire, I don’t know the prayer, but I can tell the story and that is enough,” he answered.

And so it was for my mother. She had forgotten the prayer, but she remembered the recipe and when to serve it and somehow that was enough.

Original artwork by Ashley Iokemedes

Carol Ungar is a prize-winning writer who writes

Carol Ungar is a prize-winning writer who writes

for children and adults. She’s the author of the narrative cookbook “Jewish Soul Food–Traditional Fare and What it Means” and is a mother, grandmother, and passionate home cook.