by Jonathan Ammons

Jonathan’s essay appears in episode 39 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

There are always myths in our food systems, both good and bad. One generation’s fear of fat leads to a decade of flavorless food, while for the next it is the maligned carbohydrate. Then everyone is eating avocados or açaí, but no one will consume sugar. And while these food trends and demonizations may be happening more and more often, they are nothing new. Potatoes were once known as the “lazy root”, and supposedly turned the Irish into slothful fornicators. Following the publishing of Paradise Lost in the 1600s, apples became the forbidden fruit. Nearly every religion has something that believers are not supposed to eat or drink. And in any era of mass immigration, those immigrants’ foods are always looked down upon as being strange, gross, dirty, or cruel.

Often these myths are built upon superstition, and these days we like to think that we’ve grown beyond and achieved some kind of scientific diet like we’ve outgrown such petty beliefs. But all this talk of super-foods and just one glimpse of a Goop or David Avocado Wolfe video on YouTube makes it abundantly clear that we haven’t grown at all. And that maybe our common knowledge of science grows just as slowly as it did back in the days of Galileo. And even worse, perhaps our prejudices about what we eat are tied closer to our racial prejudices than we’d like to think.

Of the many toxic food myths still thriving in our cultural broth in this country these days, perhaps the most bizarrely unfounded and specious is our aversion to Mono Sodium Glutamate. What do you know about MSG? For most of us living in America, we know the name, but that’s about it. In fact, until a few years ago, I didn’t know much more about it than the fact that most of the foods I consumed bragged that they did not contain it, with big capital letters declaring NO MSG on nearly every packaged food in the grocery store. The Similarity to labels of “No RBGH” and “No Trans Fats” should lead one to believe that MSG has something in common with those other maligned and unhealthy ingredients. But one would be wrong to think so. In fact, the truth is far from what the average consumer might think.

My perceptions of MSG shifted quite abruptly. I was working on recipes for an article, and a chef friend of mine — who just happened to be Japanese — suggested the use of MSG. When I protested, he should his head and just said, “that’s some racist bullshit, man.”

I wish I could bring chef Robert here to speak to us about it today, but sadly, he passed a couple of years ago. So instead, we’re going to talk to someone who was also abruptly corrected on his false notions about MSG.

Christopher Koetke has been working in kitchens since he was 14 years old. He’s worked in fine dining throughout France, Switzerland, and the US, and was previously the host of Live Well Network’s show “Let’s Dish”. But perhaps most importantly, he was a culinary instructor for more than 20 years at Kendall College and Laureate International Universities.

“I was teaching a course in charcuterie at the time,” chef Koetke tells, “and I was giving a lecture before we got cooking on what are the ingredients that we aren’t going to use in our meat systems? I was going through this laundry list and I said MSG. A Philippino student in my class kind of caught my eye, and I could see from the expression on her face that I’d said something, but whatever… At the end of class, she came up to me and said, ‘Chef, what’s wrong with MSG?’ And this is where I’m not proud, I was just like, well, you know… it’s not good for you… I really didn’t have an answer, but I was doing what everyone else was doing, which was simply repeating what everyone was saying. Talk about bad education, that’s a perfect example.”

“But then what happens is, she says, ‘chef, my mother had it every day in the kitchen.’ And I’m like, really? Cos I’m thinking this is really bad stuff! And she says, chef, have you ever tried it on eggs? And the only thing I did right was say, I don’t know, let’s try it. So she made scrambled eggs for me with MSG, salt, and pepper, and I kid you not, it was a moment in my culinary career where I was like, wait a minute, what is going on? This is the best egg I’ve ever tasted! So that got me really questioning that maybe I don’t understand this fully. The more digging I did, I discovered what many people are talking about today; that it’s a big myth, it’s all a big lie. It is so powerful in the food that we cook.”

So what exactly is MSG? For that, we turned to Dr. Tia Rains.

“So MSG stands for Mono Sodium Glutamate,” she explains. “And what that means is that there is one sodium — mono — and then glutamate. What glutamate is, is an amino acid. We are made up of amino acids — proteins are strings of these amino acids attached together. And so glutamate is just one of these twenty amino acids that make up protein. About 4% of our body weight right now is glutamate. It’s also the same in animals and plants, glutamate is found all throughout nature.”

Dr. Rains is quite familiar with the uphill battle of correcting the public’s errant opinions about food. Remember in the 90’s when everyone was convinced that eggs were high in cholesterol and were bad for you? Well before she dedicated her career to talking about MSG, she was the executive director of the Egg Nutrition Center where she worked to correct that bizarre notion.

“So when I started the American Egg Board, eggs were bad and people thought that they caused heart disease. When I left the egg board, the dietary guidelines for Americans had changed and acknowledged that eggs could be part of a healthy diet, and in fact, not only can they be part of a healthy diet, but there’s different nutrients within eggs that are really important to things like brain health, a developing brain during pregnancy and early childhood development, as well as brain health during the course of a lifespan. So I was able to take my learnings from working with eggs and apply a lot of them to helping people understand the facts about MSG.”

Both Dr. Rains and Chef Koetke have shifted their entire careers to work toward MSG awareness. They both now work for Ajinomoto, the inventors of MSG.

I think one of the other big misunderstandings about MSG is that it is some modern chemical developed by some Monsanto-like corporation. But oddly enough, in this case, MSG predates Ajinomoto and is the reason the company was founded in the first place.

In the late 1800s through early 1900s, Japan was in the process of a major transition. Known as the Meiji Restoration, the nation, which had been closed off from the rest of the world for centuries, began a rapid process of modernization. Adapting both their city infrastructures, education systems, and military, it was a period of insanely fast growth. It was also a period that found the Nation embroiled in two wars; the Sino-Japanese War, and the Russo-Japanese War barely a decade later. That second war ended at a time when Japan’s food systems were being seriously put to the test, as the northern breadbasket of the nation was struck by famine in 1905.

Kikunae Ikeda was a chemistry professor at Tokyo Imperial University and was one of many scientists and activists all over the nation that were trying to figure out new ways to feed people.

“They had a large proportion of the population that was malnourished,” explains Dr. Rains. “And they needed to improve the overall health of their diet. He had an interest in this and his idea was to be able to identify what the savory taste was that he had tasted in different foods and then to bottle that as a seasoning and bring it to the Japanese people as a way to help them eat more healthy foods.”

“He found that the strongest of that savory flavor was in his wife’s seaweed soup, and so he essentially dehydrated that, looked at what was left in those crystals that were left behind, and he found that the predominant crystal in there was the amino acid glutamate. So he took that glutamate and tried to match it up with a couple of different compounds to turn it into a salt. So much like we have sodium chloride, he knew he wanted to pair up the glutamate with something else so that it would make a nice salt to be used as a seasoning. He paired it up with calcium, he paired it with potassium, he paired it with an ammonium ion, but he found that the best version was when he paired it with a sodium ion. That’s because it became very soluble in water, it was easy to make a nice crystal out of it, and it tasted the best. So he coined that savory taste umami, which means ‘deliciousness,’ and then he partnered with a local businessman in Japan to bottle that up and bring it to the Japanese market.”

By 1908, Kikunae Ikeda extracted glutamic acid from kombu. By 1909, he and Saburosuke Suzuki founded the company Ajinomoto, which literally translates as “the essence of taste”.

“In Japan, it was bottled into what looked like a perfume bottle,” Dr. Rains continues. “Because then people would display it on their table tops and it would look nice. Much like we use salt here, it was used as a seasoning over there to make things taste better.”

“No one cared about it, globally,” she laughs. “It made its way around the globe, the company Ajinomoto showed up in the US in 1917. There was MSG in the food supply prominently by the 1930s-1940s, and it was really appreciated by the US military because it made food rations taste better. In fact, the military invested heavily in understanding what foods you could add MSG to, to make them taste more delicious because they saw it as an easy solution to improve the taste of these military rations that were being sent all over the world. This is around the WWII timeframe, and people loved MSG. No one was reporting any of these issues that I hear about on the day-to-day.”

MSG became a prominent part of the American diet. It was so common that it became a primary ingredient in baby food.

“MSG was sold without issue for decades around the world.” Says Dr. Rains. “And in fact, back in that time, in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, the US was the 3rd largest consumer of MSG in the world with no issues. What changed was that in 1968, when a Chinese American physician wrote a letter to the editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. And back then, as it is today, the New England Journal of Medicine is a very prominent medical journal. Medical journals have always had a part in the back where, as a reader, you could submit letters just to raise ideas and start conversation, and so that’s what this physician did. He noticed that when he was having Chinese food in the US, compared to when he was having it from his native country, that he was sometimes experiencing some symptoms — a pressure in the chest, numbness in the arms — and he wasn’t quite sure why that would be happening. So in this letter he says, it could be that there’s more salt used in the food made here, it could be excessive levels of cooking wine, or it could be excessive levels of monosodium glutamate. And at the end of the letter he says, if anyone has noticed a similar effect or has any ideas, he’d be curious to know because he was a practicing physician and not a researcher.”

“The editors of that journal titled the letter ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’. That was not an actual clinical manifestation of a disease or a condition. It was a made-up phrase that some editors at the journal came up with. It was a punchline. And unfortunately at the time, much like at the time of the early COVID-19 days, you often get this unfortunate xenophobia towards Asians when there are certain events that happen. At that time you had the Vietnam War and angst around that in this country. Chinese food restaurants, in general, tended to be less expensive strip-mall types of restaurants. They served food that seemed foreign to the type of food we were eating, and so it was really easy for people to jump on this bandwagon claiming that Chinese food makes you sick or causes these symptoms, and the chemical-sounding name, MSG, must be related.”

She continues: “It was this confluence of events that had people starting to negatively perceive MSG and Chinese food restaurants and linking them together. Then some scientists started to take the call to action from that letter and inject — and when I say inject, I mean actually inject — very large doses of MSG into the brains, into the abdomens, and under the skin of laboratory rodents. Whenever you inject a high dose of anything into any living thing, it makes them very sick. You can do the same thing with water, or air, or caffeine, or any substance. But the collection of these things happening all together really cemented this negativity towards MSG and people thought it was really harmful and it caused a lot of concern at that time in the US.”

“Many of the restaurants had no choice but to put that signage up that said, ’No MSG’, and then that further perpetuated that negativity because consumers were then seeing that message when they were going out to eat or just driving by a Chinese food restaurant with that signage out front.”

I asked Dr. Rains if those studies affected other countries or if it was just contained to the US. She explained that those studies definitely reverberated throughout the world, primarily through Europe, but many cultures didn’t adopt the zeitgeist, particularly in the East.

“On the heels of all of that, there were lots of different actual randomized trials that were conducted on MSG to try to see if there was anything there and to try to see if they could replicate any of the findings of those animal studies. Time and time again, and it didn’t matter who did the study, MSG is not associated with any of the symptoms that the letter originally laid out, and it’s certainly not associated with anything that is harmful.” Explains Dr. Rains. “That being said, people tell me all the time about how MSG causes them to have a headache or any number of things, and my response to that is, well, the randomized controlled trials did not show that. So you could be an outlier — that’s very possible, people are people and everybody is different. The relationship between food and health is individual. But it’s also quite possible that if you’re expressing symptoms of an allergy after you eat at a particular restaurant, that you actually have a food allergy that’s not MSG and you should probably figure out what that is!”

“Allergies are serious and can get worse as you get older,” she cautions. “My line of questioning is usually: you don’t feel well after you eat at a Chinese food restaurant, how about when you have ranch dressing? What about Doritos, or Cheetos, or Campbells Soup? Because it can’t be MSG because there is MSG in those foods. Also, there’s naturally and inherently present MSG within tomatoes — they are very high in glutamate. Mushrooms and Parmesan cheese are also very high in glutamate.”

——

I think it is important to give a little context to the history of Chinese and Japanese cuisine in America at this point. Chinese food first landed in this country in the 1840s, when migrant workers traveled from China to work in California during the gold rush. At one point, Chinese migrants made up 30% of the population of California, and for nearly three decades, the majority of Chinese migrants in the country were contained to that state, which created a whole industry for Chinese-speaking entrepreneurs.

But if centuries of global migrations have taught us anything, it is that majority populations fear a rise in minorities. And by 1871, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, banning Chinese immigration and limiting the work that existing migrants could perform to running restaurants and laundromats.

There was a glaring loophole in the legislation, however. It said that migrants running laundromats or restaurants would be allowed to immigrate family members to help with those businesses. Seemingly overnight, Chinese immigration associations began organizing. Rather than have all of the migrants stay in the same communities and compete with each other, they began assigning them cities all across the country where they could open restaurants and laundromats in places where they were lacking. Within a decade there were Chinese restaurants in nearly every city in the US, as those 70,000 migrants split up and spread across the map in what would be one of the largest immigrant diasporas in American history. One that opened the door for even more Chinese migrants to move to the country.

Chinese food gained particular popularity among cosmopolitans in the 1920s who found it exotic, but that popularity would wax and wane over the years, particularly following World War II. By the time Dr. Ho Man Kwok wrote his letter to the New England Journal of Medicine in 1968, there was already a burgeoning stigma against Chinese food, despite the fact that it had been on these shores and ingrained in our communities nearly 80 years longer than Italian or Greek food.

“Dan Pashman — he’s the host of the Sporkful — he goes into how, as the first immigrants show up in the US, it paints our perception of their food culture,” explains Dr. Rains. “So for example, we associate French food with being high-end and expensive because that is how French restaurants first showed up in the US. Mexican food showed up as street food in the US first, so we associate it with cheaper food, but Mexican cuisine is all over the map! The same thing happened with Chinese food, the first restaurants to show up here tended to be the cheaper restaurants, and our perceptions have always been that it is therefore somehow lower quality.”

“Unfortunately, now, if you fast forward, those perceptions are still there but we are seeing it in this idea of ‘Clean Eating’.” She continues, “People have essentially defined Northern European eating as clean eating and then everything else — especially Asian — is not clean. It’s just manifested in a different way all these years later and continues to be perpetuated for whatever reason in our country.” All of that Clean Eating talk is barely a dog whistle at this point, so much as it is blatant racism.

At this point, you may be thinking, but Jon, isn’t MSG still a lab-manufactured food product? How can it possibly be healthy? Well, don’t worry, Dr. Tia Rains has some more thoughts on that too.

“Even though MSG has a chemical-sounding name, it’s not that different from Sodium Chloride, which is salt. Now, unfortunately, when the seasoning made its way into our regulatory framework for food, it got entered as Mono Sodium Glutamate and not a common name. So that is always going to be a challenge with people because they hear it and it sounds like a chemical, but everything has a chemical name, we just drop the name in favor of something else over time because it makes us feel comfortable. Water has a chemical name, too.”

“MSG is actually made by fermentation and it comes from plants,” she says. “In the US, we make MSG in Iowa, and it comes from corn. In other parts of the world, MSG is made from crops that grow locally. So sugar cane in South America, or Cassava in Asia, and it’s made through the same type of process that beer is made, that yogurt is made, that anything that is fermented is produced. It’s plant-based — if you want to use a trendy term.”

Over the course of years, Dr. Rains and the folks at Ajinomoto have fought the negative stereotype of MSG. They even had to challenge Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary on their definition of Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, a campaign that took 4 years for Webster to finally concede, changing the definition in 2020. “They had a definition that was false and perpetuating these stereotypes against Asian cuisine,” says Dr. Rains.

Another common myth about MSG is that it is high in sodium. This is an understandable misconception since sodium is in the name, but unlike sodium chloride, monosodium glutamate contains a fraction of the sodium that salt contains.

“It only has 12% sodium within that container,” says Dr. Rains, “So it is low in salt, it’s mostly glutamate, and because umami is a basic taste, the way salt is a basic taste, there’s this interaction within the mouth that allows you to not miss the lack of salt. So in some cases, you can reduce the amount of salt by 40-60%, so it is very effective, and unfortunately, it just doesn’t get used as much in the food supply because of the negative stigma. In the US, 9 out of 10 people consume more sodium than what is healthy. By using MSG — it’s not going to solve the entire sodium issue — but it is going to help by helping Americans reduce salt in their diets without compromising on taste. We want people to enjoy their foods, but we want people to enjoy the foods that we know make people healthy. By managing sodium and increasing umami, that is one tool that we can use to help people down that path.”

Chef Koetke agrees. the salt misconception is a hard one to break.

“There’s a lot of confusion around the role of salt and MSG,” he says. “The two are not the same. There is a sodium that is shared, but MSG has 1/3 of the sodium of table salt, and I think that when you explain that salt has its own taste receptors in your palate, and umami has it’s own taste receptors, you understand that they do two different things. Which means that when you season food, you season with salt and MSG, because it’s exciting two different taste receptors. It’s about creating balance.”

Koetke has worked extensively using MSG to lower sodium rates. “When you take salt out of food, it’s less interesting. But when you backfill that with umami, all of the sudden, your mouth just has this richness of flavor. If you replace half of the salt with MSG, you’ve reduced sodium by 40%, and when you sprinkle that on food, the food tastes amazing! It’s a great tool for anyone who is thinking about backing the sodium down in their diet.”

I think it is worth pointing out that, in the wake of that letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, more and more food companies felt pressured to remove MSG from their products over the years. In packaged foods, this often greatly affected their flavors, stripping that savory taste from foods where people had come to expect it. So how does one compensate for the lack of umami? If they are trying to cut costs, they just add salt. So what does that do once those exported foods start landing in communities and cultures that don’t have as much access to fresh foods and rely on those packaged products for their diet? Heart disease begins to rise.

But beyond those global issues, MSG is a great ingredient to utilize when it comes to cooking at home. But a question I’m sure most of you might be asking is, just how the hell do I use it?

“What do I recommend for people at home?” Asks Koetke. “Just try stuff. Put it on salmon, put it on steak, put it on eggs, put it on vegetables, Brussels sprouts, cabbage. Because umami has a Japanese name, there is this myth out there that it is all about Asian food — you put MSG on Asian food — and nothing is further from the truth. You see examples of umami-rich foods all over the world, and in fact, adding MSG to a steakhouse menu, to Italian food, to French food, adding it into a classic French Bordelaise transforms it into something really, really fabulous.”

Back in the fall, I hosted a Day of the Dead pop-up at a local cidery called Barn Door Ciderworks. We decided that we wanted all of the courses to be vegetarian since it’s a fairly rare treat for veg-heads to receive a multi-course meal in our meat-centric culinary world. I wanted to make pozole to stick with the traditional foods of the holiday, but if you’ve ever had it, you know that the bulk of that soup’s flavor comes from chicken broth and a ton of shredded chicken. I substituted mushrooms as the protein and even used dried mushrooms to try to bolster the stock, but despite their concentrated umami, it was still lacking something. I was hesitant to add more salt to the stock but I decided to reach for a secret ingredient in the back of my cabinet — a jar of MSG.

And I think that is the best way I know to describe what MSG does to a dish. It doesn’t make it salty, it doesn’t make it spicy, it just provides body. It’s almost like it embellishes the flavors that are already there. And just seeing what it did for that mushroom and hominy soup made me wonder what else it could spruce up.

“Just to throw out some ideas as a starting point,” Koetke suggests. “Anything plant-based. I personally love the role that it plays with cruciferous vegetables. I think it’s amazing when you cook a steak or a piece of salmon, anything that is grilled — when you season it with salt and pepper, season it with MSG too. And then lastly is what it does with cheese. Anytime you are making a cheese sauce, that little bit of MSG really bumps up the cheesiness of it and makes it that much deeper.”

As I mentioned in the beginning, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen a reversal of a maligned ingredient in the food world. Butter and lard were once slandered as margarine was offered as an alternative. But in the end, society reversed that opinion. And we already mentioned Dr. Rain’s work on the incredible edible egg. But the human mind is such a hefty and slow-moving beast, it must be such a burden to reverse this kind of whale.

“If you had asked me this 5-10 years ago, I would have said this was going to be one long uphill battle,” says Koetke. “I actually think we are getting to the point where the see-saw is starting to tip. And I truly believe that in the next few years, you’re going to see the momentum change on that see-saw. Yes, I do foresee a time in the not-too-distant future when people say, look, we don’t believe in myths, we believe in facts. And once you know the facts, we know what MSG can do in food and why aren’t we using it?”

“It’s funny because when I think about why I said we weren’t using that day in the classroom, I didn’t really have a reason. It was just one of those myths — as many myths are — that just gets handed down, and you just don’t question it.”

“I think there’s another thing that I sense from chefs, where they feel like they are cheating,” he laughs. “They’ll say ‘I love umami, but I won’t use MSG.’ Like, somehow, that’s a badge of honor. And the next question I ask them is, ‘okay, let’s follow that reasoning. Because umami is one of your basic tastes, and salt is one of your basic tastes. So what happens if we take your salt out of the kitchen and you can use salty ingredients, but you can’t use salt because that’s cheating?’ And immediately they say, ‘No! You can’t take salt out!’ What happens when we add salt in a recipe? It adds salinity. What happens when we add MSG? We add pure umami. When I explain this to chefs, you see the lightbulb go on and they say, ‘oh, yeah! I never thought about it that way!’”

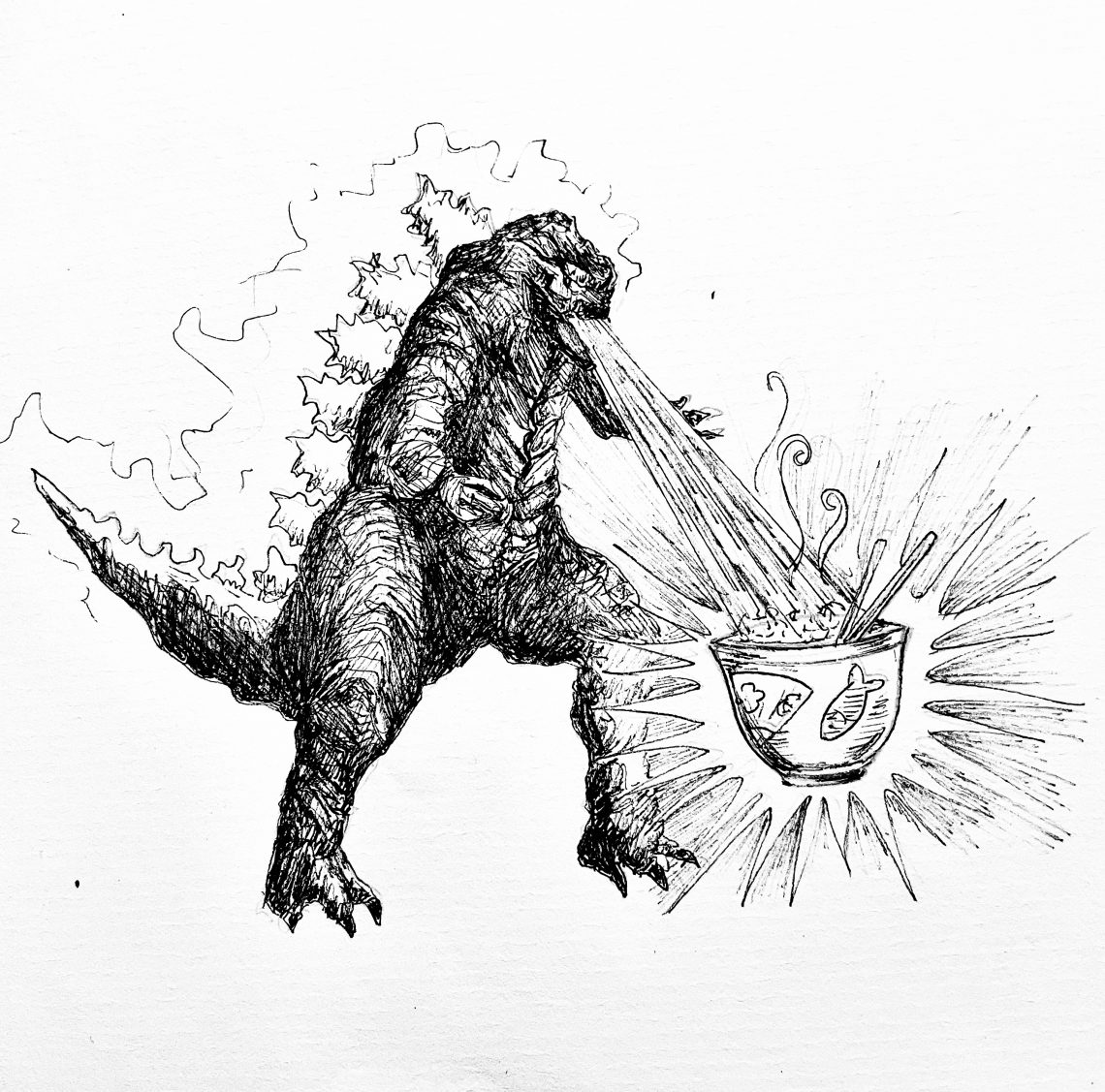

Original artwork by Claire Winkler

About the Author