by Erica Goss

Erica’s essay was originally published with The Sunlight Press and appears in episode 38 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

My mother, two younger brothers and I ended up here, in a grungy North Oakland commune, after a tumultuous year of traveling from California to Kentucky and back in the wake of my parents’ oscillating breakups and reconciliations. My college-professor father lives in Richmond with a girlfriend. They break up and he moves in with us. It’s 1972 and there are no jobs for college professors. We squeak by on my mother’s welfare check while my father sends out resumes.

At twelve, I’m tall for my age. Everyone tells me I look sixteen. This must be why men follow me on the street. Sometimes they touch me, or pull my arms away from where I hold them, crossed tightly over my chest. The men are old, young, students, hippies, businessmen, white, brown, black – they all terrify me, but I’m more afraid of staying indoors with my parents, who argue incessantly while my little brother screams.

Donna, the hippie Earth mother of our commune, decides to plant a garden in the backyard. She wrestles some space from the blackberries and puts in tomatoes, lettuce, beans, and zucchini. Only the zucchini survives. It grows to enormous proportions, snakes under the blackberry vines, deposits its huge fruit between the cracks in the sagging front porch stairs, and surrounds the house in thick green stems loaded with yellow blossoms. No one has ever seen anything like it. I add squash to my list of fears.

Before we moved to Oakland, I had never tasted zucchini. No one in our commune, a shifting population of between ten and fifteen people, knows what to do with the dozens of enormous squash. Throwing them away is out of the question, and in spite of our large household, there is simply too much for us to consume.

My mother gets the idea to take them to the apartments across the street and asks me to help her. “No way,” I snort, trying to hide my terror at actually speaking to the people who live there. So she asks Donna, the planter of the zucchini, who readily agrees. The two of them fill a large cardboard box with a dozen or so giant green vegetables and head out the door.

The apartments are built in a U-shape around a courtyard with a full view of the street. During the day, children play on the concrete; at night, young men huddle in groups of two or three, openly dealing drugs. Peeking through the curtains of our front room, I watch my mother and Donna knock on doors, the box of zucchini on the ground between them. Curious faces peer from windows. A thin, elderly woman looks into the box, reaches in and pulls out a big, green squash. A smile spreads across her face, and she and my mother engage in a conversation. More people come out of their apartments. A few take some zucchini, but more simply stand outside and talk.

There are no major grocery stores in our neighborhood. The corner stores sell alcohol, cigarettes, snack foods, and candy from behind Plexiglas. The residents of our area have little choice but to shop at these stores for their daily groceries. Fresh fruits and vegetables are simply not available to apartment dwellers with limited transportation options. Years later I hear this and other parts of Oakland referred to as “food deserts.”

Every few days, my mother sends my brother or me to the store nearest our house with a handful of food stamps. For a couple of dollars, we buy four candy bars, a half-gallon of milk, and a loaf of bread. I don’t make eye contact with the clerk as she slides the receipt across the counter towards me.

The box of zucchini is almost empty when Donna and my mother return, full of stories about the people who’d overcome their suspicion of the women from the hippie house. Some of the women from the apartment building shared recipes for stuffed zucchini, batter-fried zucchini, sautéed zucchini with onions, and zucchini bread. One teenaged boy suggested that the biggest squash could become speed bumps, and slow down the traffic on Alcatraz Avenue.

For a few moments, my mother seems happy. The weight of the previous months lifts from her face as she smiles, surprised that her impulse to give the zucchini to our neighbors went so well. We go into the kitchen and look up a recipe for zucchini bread in one of the commune’s tattered cookbooks. Soon a delicious fragrance fills the house as the bread bakes.

That night, we sit around the kitchen table with some of the other residents. The bread is sweet and slightly mushy in the center, with a sugary crust. Bits of green zucchini appear as we cut the loaf into slices. Even my brother, a picky eater who won’t eat weird things like mushrooms and carrot cake, consumes a tiny morsel.

My mother discovers that zucchini is a nutritional powerhouse, containing vitamins C and B6, as well as manganese, riboflavin and potassium. Now that she knows this, zucchini appears at the dinner table nightly. My adolescent body craves nutrients, and I’m constantly hungry. I wolf it down, though my brothers won’t touch it. I make zucchini bread or muffins almost every day.

The next time I walk past the apartment building, I say nothing and keep my eyes down. But I don’t feel quite as afraid. When a man yells at me from a passing car, I think about the recipe for zucchini bread. And I keep on walking.

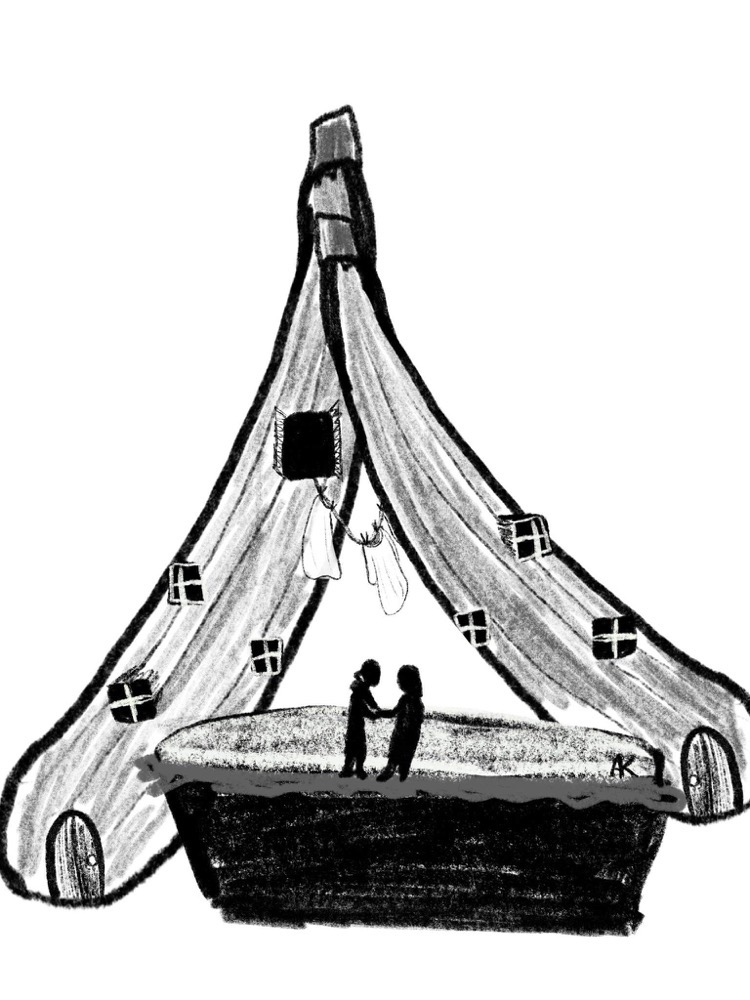

Original artwork by Alex Knighten

About the Author

Erica Goss is the author of Night Court. Her flash essay, “Just a Big Cat,” was one of Creative Nonfiction’s top-read stories for 2021. Recent and upcoming publications include The Georgia Review, Oregon Humanities, Creative Nonfiction, Redactions, and Consequence. Erica lives in Eugene, Oregon and edits the newsletter, Sticks & Stones.

Erica Goss is the author of Night Court. Her flash essay, “Just a Big Cat,” was one of Creative Nonfiction’s top-read stories for 2021. Recent and upcoming publications include The Georgia Review, Oregon Humanities, Creative Nonfiction, Redactions, and Consequence. Erica lives in Eugene, Oregon and edits the newsletter, Sticks & Stones.