by Piper J. Daniels

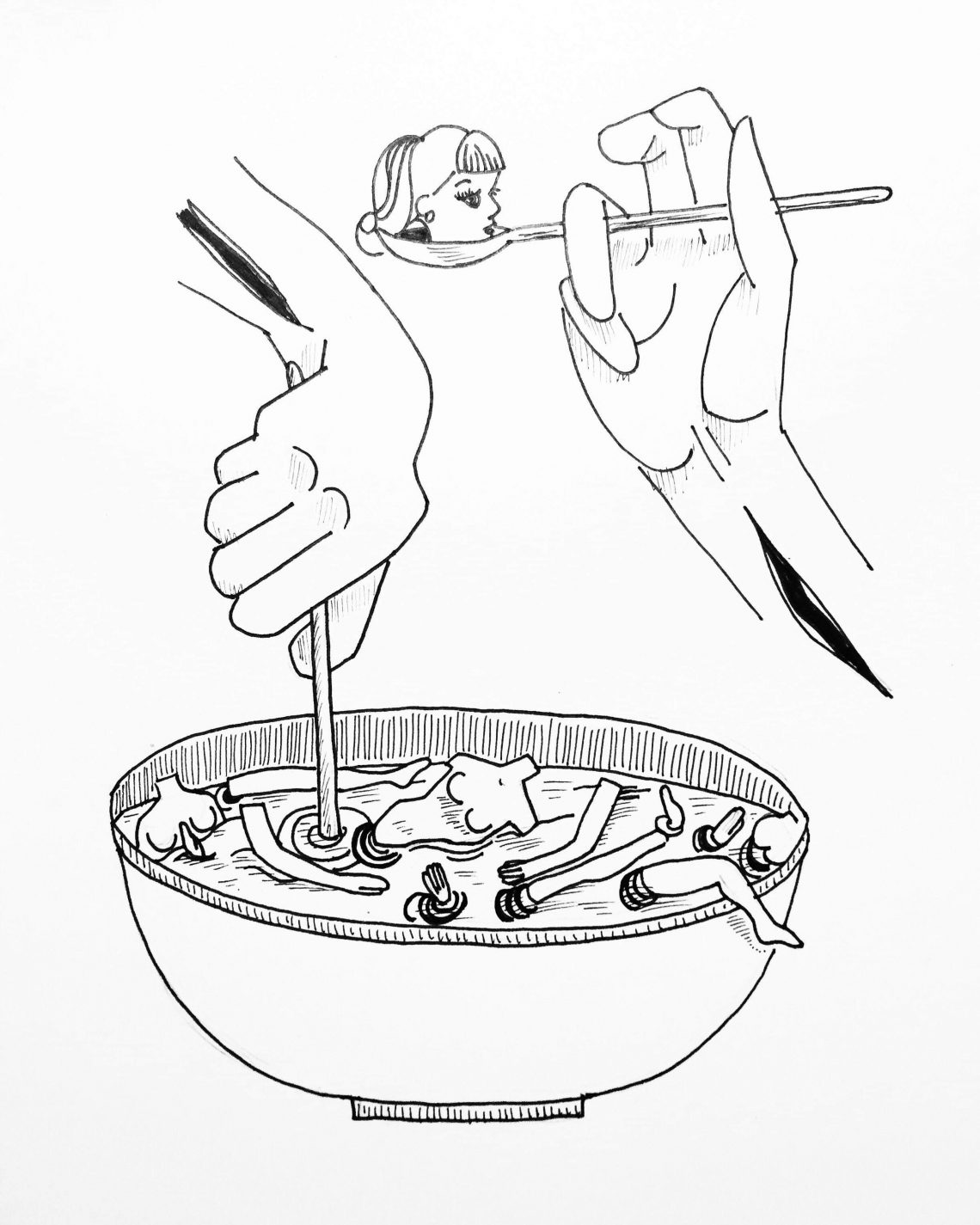

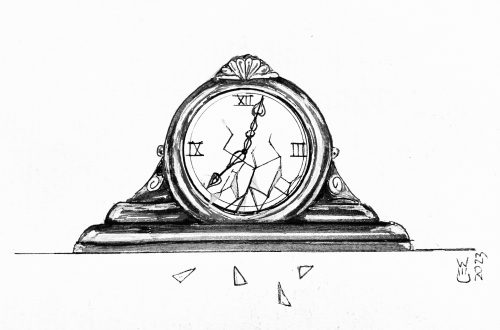

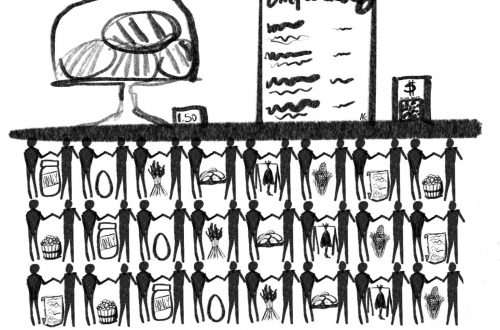

Art by Maryanne Poppano

Piper’s story appears in Episode 7 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, which aired on November 2, 2018.

I can only say in the dark

how one Spring

I crushed a monarch midflight

just to know how it felt

to have something change

in my hands.

-Ocean Vuong

Disordered eating was as much a part of my upbringing as arithmetic or prayer.

Each bland dinner began with the blood and the body of Christ.

Every night my mother served us the same meal—steamed chicken and vegetables, which were carefully weighed on a small white scale in order to track portion size and caloric intake with precision.

Upon the kitchen counter was a cookie jar in the shape of a cow that mooed when you opened the lid. Only very rarely did it contain cookies.

It was meant to be a lesson.

It was meant to be a trap.

Memories of mealtime are so vivid that even in my adult life, it is difficult to separate present from past, as though eating could only exist inside the same shameful moment.

***

A girl is given a mantra, which is like a prayer:

A moment on the lips, a lifetime on the hips.

Nothing tastes as good as being thin feels.[i]

A girl is given a diet and, as the trends change, another and another:

Alkaline. Atkins. Baby Food. Blood Type. Cabbage Soup. Master Cleanse. Mediterranean. Paleolithic. Slimfast. South Beach. Weight Watchers. Zone.

A girl is given aid:

Adderall. Dexatrim. Hodroxycut. Metabolife.

A girl is given the opportunity to push herself:

The ipecac diet. The finger down your throat diet. The swallowing of saturated cotton balls diet. The laxative diet. The cigarette diet. Even the Breatharian diet, in which nourishment is derived solely from sunlight and air.

If it is as Plath ventures, that “dying/ is an art,” then disordered eating is the central artistic medium in which girls are instructed and supported. As women, we pass this curse from generation to generation, enforcing the very practices that made us ill and held us down.

For over a decade prior to her first pregnancy, my mother controlled her figure and her hunger by chewing sugar-free cinnamon gum and eating exactly seven saltine crackers a day. In sharp contrast, pregnancy must’ve felt to my mother like being violently possessed.

She tells stories about blacking out and coming to in the McDonald’s parking lot, the flavor of burgers and apple pies on her tongue.

She had nightmares that we were born so small and starving we disappeared in the sheets.

When it was time to be born, my mother’s hips proved too small, so my sister and me were ripped from her body like bad spirits in a séance gone wrong.

My mother did her best to make healthy choices while I was in utero, but I know plenty of women with mothers who refused to “eat for two,” women whose first diet began in the womb, where they grew from a cradle of bone.

***

The great love of my childhood was my grandmother, the well meaning, rightwing matriarch who firmly believed that beauty was a woman’s greatest power. She took me to the K-Mart superstore every Friday so I could select another doll to inhabit my Barbie universe. By age six, I had everything a little girl could dream of: dozens of Barbies, three corvettes and a safari jeep, a spa, an ice cream store, and a cul-de-sac of Dream Houses. An embarrassment of riches but for one thing: I fucking hated Barbie, along with that basic tween, Skipper, and the most likely closeted Ken.

Barbie’s sexuality was confusing to me. Why the irremovable underpants? Why large breasts but no vagina? What did that say about vaginas? About breasts? And why, I wondered, did my friends make their Barbies and Kens scissor? Why did my babysitter enjoy making Ken talk dirty to me?

***

Germaine Greer: Whenever we treat women’s bodies as aesthetic objects without function we deform them.

***

In their interactive, multi-media collaboration entitled Doll Games, artists Shelley and Pamela Jackson describe the eroticism of their dolls, claiming they knew the dolls’ bodies better than their own. The Jacksons speak of their Barbies’ private lives as “perfect.”

“I identified with their hard dumb inexpressiveness,” Shelley Jackson writes. “It was how I felt too: my real life did not show on the outside. The dolls clacked together, their bodies all beak, all shell. Despite this, everything about them was erotic.”

The Jacksons say of their dolls, “their secrets were ours.”

Was it for lack of imagination that I eyed my Barbies suspiciously, doing my best to match the stoicism hidden carefully beneath all their lipsticked, saccharine cheer?

***

In her doll-hating Opus, The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison writes, “Adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs—all the world agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured.”

When the novel’s Claudia is gifted such a doll for Christmas, it is with this breathless incantation: “This is beautiful, and if you are on this day ‘worthy,’ you may have it.”

“What was I supposed to do with it?” Claudia wonders. “Pretend to be its mother?”

Eventually, Claudia rips that blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll to pieces. It is hard to imagine a reader who does not cheer her on.

***

No part of me believed the Barbies were beautiful. Each time I held them, it was an interrogation of their shallow superiority, their embodiment of the feminine mystique. I felt they had to answer for the damaging ideals their bodies engendered, considered them monsters who deserved to be maimed. It might be said that the hatred of something as feminine as Barbie is not in keeping with the spirit of feminism, but then, I reasoned, these Barbies were not women. They were weekly reminders of a certain plastic perfection my chubby, queer, nerdy self would never attain.

“Dolls work like possession: the little girl’s daemon occupies the helpless vessel of the doll,” writes Shelly Jackson, but for the life of me, I could never find a way in.

***

One afternoon, pushed to my breaking point by a lunchroom bully who chanted “Miss Piggy,” every time I ate, my sister and I declared war on our whole Barbie universe. She designed an amazing Chinese Water Torture Chamber. I made bombs from thumbtacks, pop rocks, and tea lights and left them in the elevator of every Dream House. When at last we deemed their torture sufficient, we cut the dolls in pieces with pruning shears, dumped their parts in a fish tank at the end of my bed and, because we were benevolent dictators, spent the rest of the week composing elegies.

***

Simone Weil: We must not wish for the disappearance of our troubles but for the grace to transform them.

***

In his poem, “Playing With Dolls,” David Trinidad describes how every weekend morning, he’d sneak downstairs to play with his sisters’ Barbie dolls.”

I’d finger each glove and hat and

necklace and high heel, then put them on the dolls.

Then I’d invent elaborate stories. A “creative” boy,

I could entertain myself for hours. I liked to play

secretly like that, though I often got caught. All

my father’s tirades (“Boys don’t play with Barbies!

It isn’t normal!”) faded as I slipped Barbie’s

perfect figure into her stunning ice blue and

sea green satin and tulle formal gown.

To no one’s surprise, Trinidad’s poem does not have a happy ending.

You’re a boy,

David. Forget about Barbies. Stop playing with dolls.

What is the lesbian’s relationship to Barbie?

She cannot possibly embrace Barbie as subversive in the way David Trinidad could.

She cannot locate her fantasy in a eunuch Ken anymore than in the sleek contours of a doll who is meant to instruct or erase rather than entice.

So many girls I’ve dated speak of leaving Barbie dolls in their boxes, unloved and untouched, their poor Mothers crying straight through Christmas morning. This is what it looks like to be queer in Barbie universe—boys like David Trinidad dressing their sisters’ Barbies in secrecy, and girls whose symbolically loaded Barbies are forced upon them.

***

In my early twenties, I subsisted on a diet of apples, green and whiskeys, neat.

Though I denied it at the time, thinness was the most important thing to me.

I was seeing five different women then, all of them sexy and thin, and my anorectic mindset masqueraded as a mode of control. If I could live on three hundred calories, I reasoned, I’d remain beautiful enough to keep each of them in my bed.

My refrigerator was barren, my cupboards aching with emptiness.

“Keep going,” the hot bartender told me. “You are almost perfect.”

Then I met J., who hated thinness. Who railed against the diet industry, and eating disorders, and girls with skinny asses. She would not accept my anorexia. She force-fed me healthy foods, spinach and sesame tofu and, compared to the other girls, her love for me felt positively nourishing.

She wanted a curvy girl. Tits and ass. Hourglass body. Is what she said.

Yet upon her living room wall was a framed poster of pin-up Betty Page in a size-small leather bikini. What was sexy about her, I wondered, to someone like J.? Were I reduced to my skeleton, I would never be as thin as the pinup of her dreams.

The truth about anorexia is that even when the behavior is dormant, the mind lies in wait for any excuse to resume.

I took the poster as permission to continue starving myself.

When we moved in together, she hung Betty on our bedroom wall. For the next six years, two cities, and three apartments, Betty presided over us, judging us, I believed, as we fought, fucked, and slept.

***

Marya Hornbacher: We turn skeletons into goddesses and look to them as if they might teach us how not to need.

***

In his 1987 film, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, Todd Haynes replaces performers with Barbie Dolls in order to reenact the final seventeen years of Karen Carpenter’s life before her death from anorexia-related causes in February of 1983. To reflect Carpenter’s bodily deterioration, Haynes slims the Karen doll gradually, with a knife. The result is an uncanny hollowing out that perfectly embodies Carpenter’s decline.

“It hardly seems more absurd,” a critic noted, “to embody Karen Carpenter as an increasingly emaciated Barbie doll… than to have her played by a workaday actress in a paint-by-numbers biopic.”

In addition to the film’s creative use of dolls, Haynes communicates with the viewer via occasional title cards, which prove insightful. The first reads:

The self-imposed regime of the anorexic reveals a complex internal apparatus of resistance and control. Her intensive need for self-discipline consumes and replaces all her other needs and desires. Anorexia thus can be seen as an addiction and abuse of self-control, a fascism over the body in which the sufferer plays the parts of both dictator and the emaciated victim who she so often resembles.

To those who would argue that anorexia is about emulating the slim figures of movie stars, or desperately attempting to become conventionally beautiful, Haynes offers an alternative theory:

In a culture that continues to control women through the commoditization of their bodies, the anorexic body excludes itself, rejecting the doctrines of femininity, driven by a vision of complete mastery and control.

***

Richard Siken: The fear: that nothing survives. The greater fear: that something does.

***

There have been times in my life when I was subjected to serious violence. In the aftermath, it was as though my muscles never made memory to begin with. My body forgot how to be a body, refusing the usual body things. Fucking Dancing. Bathing.

Touching. And being touched.

After the violence, I was horrified by the time I’d wasted obsessing over my body’s thinness, its sexiness. How badly I treated my body back when it was relatively unscathed.

Rather than grow thinner, more delicate, I ate endlessly in bed, gaining over thirty pounds in a few months’ time.

My mother spoke a lot back then about how gaining weight, how aging, renders the female body invisible.

It was all I wanted. To blend into the ether and disappear.

Roxane Gay:

When you’re fat, no one will pay attention to disordered eating or they will look the other way or they will look right through you. You get to hide in plain sight. I have hidden in plain sight, in one way or another, for most of my life. Willing myself to not do that anymore, willing myself to be seen, is difficult.

Often, what got me through the week was the idea of never being seen again.

I left my house exactly once a day, driving the long, curving road that led to Carkeek Park. Wandering beneath the watery sun, I scouted locations.

Here, I’d say to myself. Just beyond the tide pools, where no child would find me.

Here, just before the orchard, alongside the salmon run.

Every day, new coordinates for the same shallow grave.

Every day, a new plan for disappearing.

It was the lowest point of my life, but it didn’t last forever.

***

Fanny Howe: “The evidence of a successful miracle is the return of hunger.”

***

After the emergence of multiple studies that linked Barbie’s impossibly unrealistic body to an unhealthy body image in young girls, Mattel, Inc. finally announced a campaign to manufacture Barbies that represent “real women.”

Mattel, Inc. would have us believe that they’ve invested in diversity and body positivity, but is that true? Can an organization that has knowingly compromised the body image of young girls have anyone’s interests at heart but the shareholders and executives? One look at the new, “real,” Barbie (a size ten, tops) tells me she is every bit as revolutionary as the new and improved, man-bun sporting Ken.

The real solution for girls is one that would put Mattel, Inc. out of business.

Fuck Barbie.

Teach a girl to code.

Put books, instruments, and microscopes in Barbie’s place.

***

I used to believe that there was catharsis in destroying Barbie dolls, that it was a healthy way to reject the patriarchy. I see now that through such catharsis, the blame is merely redirected at women— in this case, women who embody the Barbie-esque.

Why should any form of beauty be subject to destruction?

Naomi Wolf: A culture fixated on female thinness is not an obsession about female beauty, but an obsession about female obedience.

The greatest lie the devil ever told is that women are by nature aggressive, competitive, and “catty” with one another. It is a myth that shifts insidiously from generation to generation. Every time women choose to invest in this myth, the joke is one hundred percent on us.

We need to stop making ourselves so thin that we slip through the cracks of history.

We need to stop starving our spirits and intellects long enough to find a way out.

Queer women, while not immune to patriarchy or the male gaze, are slightly less entangled it. We have more freedom to author and reject standards of beauty, and we’re well versed in forming communities in which we depend on one another. Because of this good-fortune, it seems, we have a greater responsibility to light the way.

As I continue to seek wisdom about my body and the bodies of others, this is what I know to be true:

Each time you set eyes upon a woman, look for the thing that is strong and beautiful.

If a woman criticizes your body, disarm her with the sweetest, truest compliment you can muster.

If you feel driven to criticize a woman’s body, know that that thought was planted in you, break free of it, and feel love for her body instead.

Most of all, be hungry.

“It is impossible to forgive whoever has done us harm,” writes Simone Weil, “if that harm has lowered us. We have to think that it has not lowered us, but has revealed our true level.”

The revolution begins, the true level is revealed, the moment women consent to forgive one another.

Custom illustration art by Maryanne Pappano.

Piper J. Daniels is the award-winning author of Ladies Lazarus (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2018). A Michigan native and queer intersectional feminist, Daniels holds a BA from Columbia College Chicago and an MFA from University of Washington and serves as a passionate advocate on issues of mental health, sexual assault, and body positivity. Her debut essay collection was described by Publisher’s Weekly as “beautifully written…Despite the dark content, Daniels astutely focuses on the ways women “resurrect” themselves from social, physical, and mental obstructions, as she emerges as an empowering and noteworthy voice.” Her work appears in or is forthcoming from Hotel Amerika, The Rumpus, Tarpaulin Sky, Longreads, Enclave, The Dirty Spoon, The Monarch Review, and elsewhere. She lives in the American Southwest with her incredible partner, a coven of mischievous puppies, and a very stylish cat. Learn more at https://piperjdaniels.com.

[i] Attributed to Kate Moss