By Jonathan Ammons

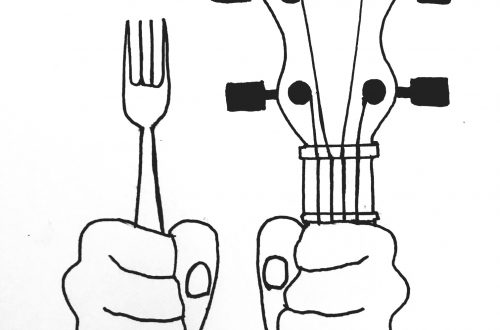

Art by Corinne Pease

Jon’s essay, “A Mantra,” appears in The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, episode 3, which aired July 6, 2018.

Make stock, bake bread, and preserve what you love.

This fall I was once again invited to the Terravita Festival in Chapel Hill. The 3 day symposium of culinary nerdism has become one of my favorite food events in an industry chock-full of exceedingly mediocre festivals. I won’t get into my hatred of the food festival here, but consider it fierce and long suffering. But there is something about Colleen Minton’s TerraVita… based around the idea of cultivating a slow foods, farm to table, and more mindful way of eating, the grand tasting brings together some of the Triangle’s more interesting kitchens, the dinners feature authors that take their books beyond recipes and into the heritage of many foods, and their classes range from social justice in the restaurant industry to tracing the roots of where our foods come from (hint: in the south, a lot of it comes from Africa).

But the thing that caught me by the sleeve and wouldn’t let me go this year was the course on Appalachian culture. Victuals author Ronni Lundy, Blind Pig founder Mike Moore, Ian Boden of Virginia’s The Shack. And Seasonal School of Culinary Arts director Susi Gott Siguret were all there (well… Ronni got waylaid when her oft praised Astro van broke down) They were talking about what it means to be Appalachian. In the time I have been writing about food, and in particular, food in Appalachia, I have never been able to truly pinpoint what is distinct about Appalachian cuisine, or culture for that matter, other than that it is often sour, aged, and long held, much like our prejudices. So upon leaving Chapel Hill and returning to the hills where I was raised, I started poring over the idea with a little more intent.

In the time I have been writing about food, and in particular, food in Appalachia, I have never been able to truly pinpoint what is distinct about Appalachian cuisine, or culture for that matter, other than that it is often sour, aged, and long held, much like our prejudices.

What were the things I learned from my elders?

My grandmother, the women at her church, my aunts and uncles, my father and mother, the people I’ve met along the way, what did they teach me?

For most of that wisdom, I can whittle it down to a phrase, one that could perhaps even serve as a mantra:

make stock, bake bread, and preserve what you love

Pickles and Preserves

Let’s start with that last bit. Both my grandmother, and my great grandmother were a canners. In fact, their primary recipe books were a canning books. I’ve always liked that, because they understood that canning was a form of cooking, and that the flavors you included in the jar would be the things your guests might taste come Thanksgiving dinner. There’s something quite personal about the flavors you hand select to include in your canned green beans versus the can you might have picked up for $0.89 at the grocery on the way home. Do you can with garlic? Black pepper? Red pepper for spice? Do you use herbs or ginger? Everyone seems to do it differently. But the most important part of canning seems to be what one chooses to preserve, after all, we tend to save what we love.

One of my favorite results of this Appalachian tradition of canning and pickling, is that it means that foods that would otherwise be purely seasonal become year round features on the dinner table. The tomatoes you harvested from the garden in June are savored in March in a scratch made tomato sauce, eggs in purgatory bubbling away. The wild strawberries from that hike in July come back to life on warm biscuits after you’ve been sledding.

But it also goes a little deeper. That preservation means a lot more than just the summer harvest. Preserving what you love means saving those parts of your culture that are ingrained in you, concentrating them, and keeping them for the future. These often cloth themselves in simple gestures, manners, or habits. Like when your neighbor comes looking for a part for his broken shelf in his shed, and you happen to have one, you give it to him and you understand that you can settle it later, or that it all might shake out in the wash. Or when your church, or the town hall meeting ends, you all stay to fold up the chairs and sweep up the floor, because if you don’t, someone else will have to. Or when your friend is having a fight with his wife, you let him crash on your couch so that they can have some space with people they know and trust, and really take their time to work things out. These are innate in your culture at their best times, when they are ripe, and just like the peak harvest of your garden, the best you have to offer should be preserved, even if that means pickling.

Preserving what you love means saving those parts of your culture that are ingrained in you, concentrating them, and keeping them for the future.

Bake Bread

Every culture has a bread. It is one of the building blocks of civilization. In fact, the desire to manage and grow wheat in order to make bread was really what brought the first tribes of people together in Sumer and Egypt to develop the first systems of government in human history (Someone had to manage all that grain!). Exchanging for bread was the inspiration for money as a token of value (hence the slang bread as a term for cash). And even Jesus coined the term for soaking up time with your friends and family as breaking bread.

I was in Vermont a while back, bumming around the Appalachian Mountains in the Northern Kingdom, right on the border with Canada. My friend Jen had coaxed me into the hills to visit the Bread & Puppet Museum in the tiny town of Glover. For those not familiar with Bread & Puppet, they were a group of artists that banded together around Peter Schumann in 1962 to protest the Vietnam War through a love of art and puppetry. But these are not just any puppets.

Towering, multi-story paper mache creatures loom from the ceilings. Warped creatures depicting the horrors of war, the pompous corruption and callus views of world leaders, and the ravaged remnants of the people caught in the wake of global conflict. The museum is most definitely worth the drive should you find yourself in Vermont. But what is important for our needs in this story is not the puppets, but the name.

Bread & Puppet came from Shumann’s philosophy that art should be like good bread; nourishing, carefully made, delicious, and cheap, so that anyone can be fed. Because, that is the thing about bread, it is the great leveler of food. Both the finest, white tablecloth restaurants, as well as the diviest soul spots, and even fast food joints all serve bread. It is the universal language for nourishment, a common tongue among all cultures (and for all you celiacs about to send me nasty messages about bread, I’ve got a nice batch of cornbread crackling in the oven for you right now).

But what makes bread so great to me is the care and attention to detail it takes to make it. Unlike stock, it requires precise measurements, careful handling, and most importantly, time. It is a time honored tradition, and something that, when shared, is the ultimate culinary declaration of affection and commeroderie. The only thing we have in this life of true value is our time.

Because, that is the thing about bread, it is the great leveler of food.

Make Stock

My father seems to have always understood, and made great effort to convey to his children, that value is not inherent in something, rather it is created. That every situation has its fair share of downs and disappointments, but that even the worst of what we go through can be pressed into something of value.

I keep a ziplock bag in my freezer that I cram full of every trimming from every carrot, radish, celery, and turnip, each onion, cauliflower, broccoli, and garlic end, as well as every corn husk, onion skin, chicken bone, or shrimp shell. When the bag is full, I dump it all in a big stock pot, and slowly simmer the random assortment of scraps overnight. By the next morning, there is an otherworldly reduction of compacted and concentrated flavor. Once strained and seasoned with salt and pepper, I freeze that stock in pint sized pours in ziplock bags that I lay flat in the freezer so that I can later line them up like books in a library on my freezer shelves. I can make soups with these, spice up a packet of ramen on a drunk night, or even just drink them when I am not feeling well. I use them in my chicken & dumplings, in my coq au vin, and even to make my grits.

I freeze that stock in pint sized pours in ziplock bags that I lay flat in the freezer so that I can later line them up like books in a library on my freezer shelves.

The cornerstone of cooking is stock, and the cornerstone of stock is your trash. There is no more literal example of turning trash into treasure more prescient than stock. And there is nothing more pertinent to Appalachian culture than creating something of value from what others tend to waste.

Artwork by Corinne Pease