By Jonathan Ammons

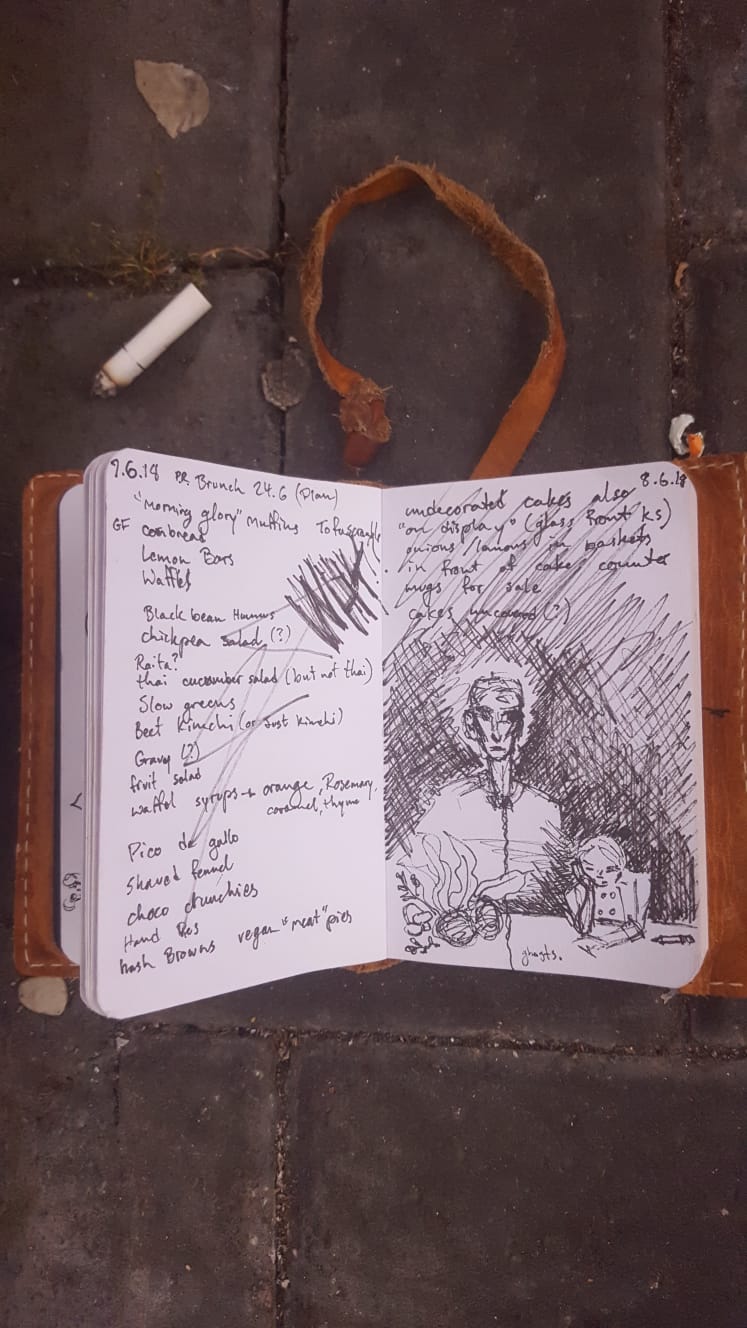

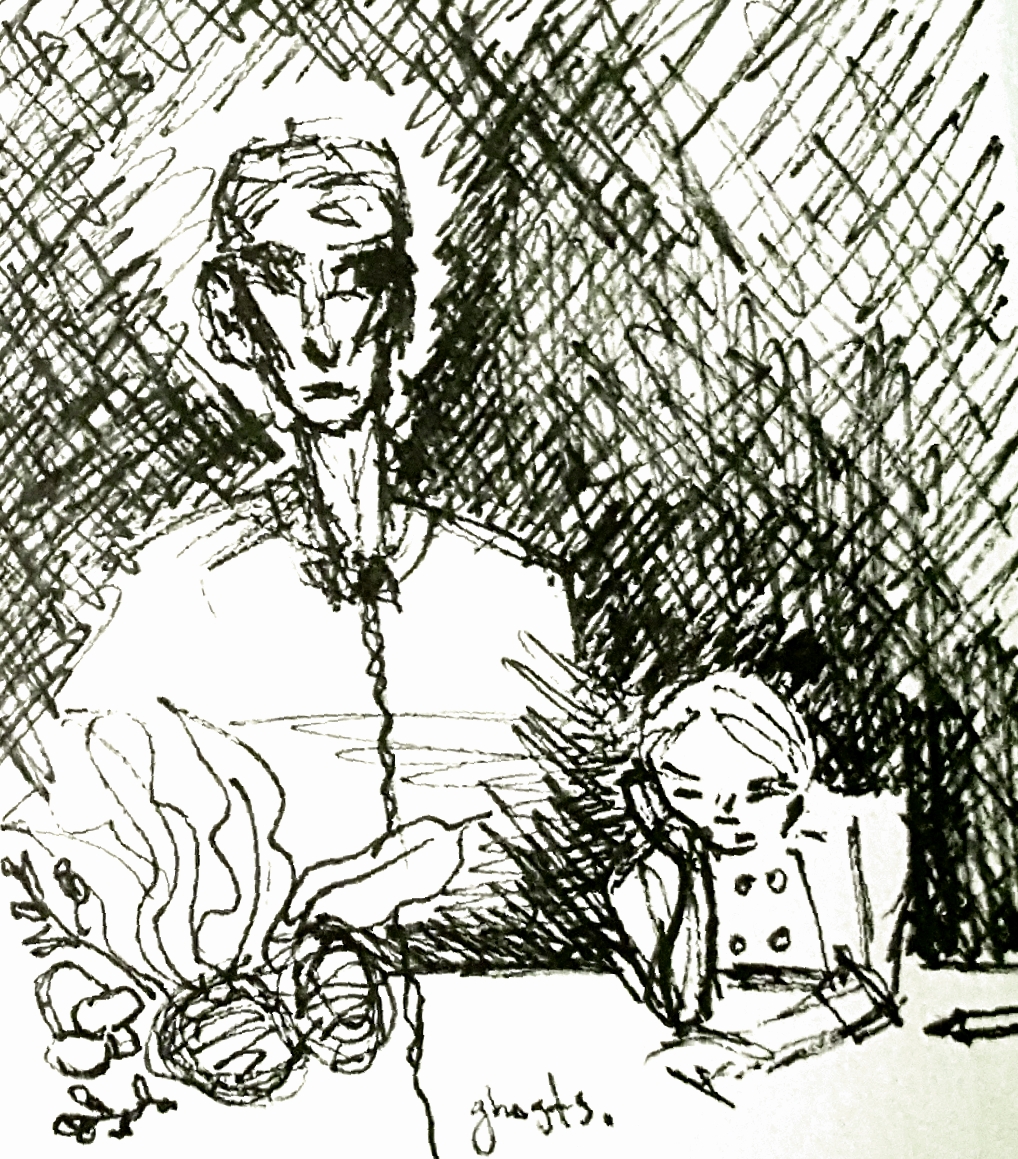

Art by Katrin Dohse

Jon’s essay, “Bourdain,” appears in The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, episode 2, which aired June 15, 2018.

“[When I die], I will decidedly not be regretting missed opportunities for a good time. My regrets will be more along the lines of a sad list of people hurt, people let down, assets wasted and advantages squandered.”

— Anthony Bourdain

“I wasn’t in Haifa, I wasn’t in the north of Israel, I don’t know what that was like, I was in Beirut. In the few years since I’d started to travel this world, I’d found myself changing. The cramped, cynical worldview of a man who’d only seen life through the narrow prism of the restaurant kitchen had altered. I’d been so many places, I’d met so many people from wildly divergent backgrounds, countries and cultures. Everywhere I’d been, I’d been, as in Beirut, treated so well. I’d been the recipient of random acts of kindness from strangers, and I’d begun to think that no matter where I’d been or who I’d sat down with, that food and a few drinks seemed always to bring people together. That this planet was filled with basically good and decent people doing the best they could if frequently under difficult circumstances. That the human animal was perhaps a better and nicer species than I’d once thought. I’d begun to believe that the dinner table was the great leveler. Where people from opposite sides of the world could always sit down and talk, and eat, and drink, and if not solve all the worlds problems, at least, find for a time, common ground. Now, I’m not so sure. Maybe the world’s not like that at all. Maybe in the real world, the one without camera’s and happy food and travel shows, everybody, the good and the bad together, are all crushed under the same terrible wheel. I hope, I really hope I’m wrong about that.”

— Anthony Bourdain

He was a cook. He barely considered himself a chef, and he certainly wouldn’t call himself a journalist.

But there, in Beirut, watching planes pass overhead, dropping bombs on the neighborhoods he and his crew had just spent the last week getting to know and filming, a lot changed for him. A lot changed when he found himself in Namibia, Iran, Mexico, Laos, or Myanmar. And he showed us those changes, and he showed us how those understandings, those revelations hurt. How they reflected on us as a civilization. He wasn’t blaming us, but he was accounting for our behavior.

On the morning of June 8th, when his best friend, chef Eric Ripert, found him hanging lifeless in his hotel room in Kayserberg France, Anthony Bourdain had sealed his own legacy.

I honestly don’t know if I would have my career without Tony. All of us here at Dirty Spoon have deeply influenced by his work, but I don’t know if I would have ever thought to write about food and booze for a living if not for him. If I hadn’t seen an episode of A Cooks Tour in college and bought the book, and found it to be one of the best memoirs I’d ever stumbled upon, I don’t know what I’d be doing right now. But it was Bourdain who clued me in. Seeing some old punk jackass in a Ramones t-shirt cruising down the Mekong River, stopping to eat some noodles while making casual comments on the scene, opened up whole new understandings of foreign cultures to ignorant shits like me. It really made you understand that with a little bit of speculation, a lot of openness to adventure, and the willingness to listen, the world could be much bigger than you ever knew.

All of us here at Dirty Spoon have deeply influenced by his work, but I don’t know if I would have ever thought to write about food and booze for a living if not for him.

The best part was watching him grow. From the cocky, arrogant, old guy in Kitchen Confidential, he found himself on boats, planes, trains, and in sticky situations in A Cooks Tour, before landing his shows on Travel Channel and then CNN, and through all of it, we saw a 40 year-old punk turn into one of the most thoughtful, tender, and open human beings on earth. His focus went from seeking out good food to seeking out deep culture. In the long faded wakes of MFK Fisher, Bourdain took the same mantle and folkloric narrative of a food writer at the dinner table to plunge headlong into politics, morality, philosophy, and tradition. He used journalists techniques to make something very different from journalism.

By being a memoirist and not a field reporter, Bourdain was able to find himself in regions of the world most of us don’t take the time to think about. When’s the last time you mulled over the struggles of the Namibian people? Or folks in the Congo? But nevertheless, that’s where he went. By sitting at the tables of people all across the world, he gave us windows into their worlds, pictures of everyday life in countries the majority of us will never even consider setting foot. So that now, when we hear about a bombing in Libya, or see a hurricane approaching Cuba, we think of the people we saw at his table, kind people who cooked for him, sheltered him, and treated him like one of their own.

By being a memoirist and not a field reporter, Bourdain was able to find himself in regions of the world most of us don’t take the time to think about.

He taught us not to be afraid of the other. He taught us how painful it is to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, but he also showed us how valuable that is, and how it is worth the pain.

I found out about his death when Catherine texted me at eight that morning. When I learned it was Eric, his best friend who found him, it broke me. But when I scanned social media and saw that just about everyone I knew, from every walk of life, in every industry, religion, denomination, and political party, were singing his praises and lamenting his early passing, it brought a strange comfort. Everyone in the food industry wanted to be Anthony Bourdain. They wanted his lifestyle, his freedom, his gravitas, his compassion. Everyone wanted it but him.

He didn’t pretend to be a saint.

He’d burned through 2 marriages, both ruined by affairs. He was a recovered heroin addict. He was as blue collar as they came. He wasn’t some hot shot chef, he was just a dude. He was just one of the boys on the line at the bistro, and he worked his way up from a dishwasher to a chef, and eventually to an award winning writer through discipline and tenacity.

They wanted his lifestyle, his freedom, his gravitas, his compassion. Everyone wanted it but him.

The best part about the social media storm that erupted after his passing were the pictures. Most were press photos, as I scrolled through my Instagram timeline, but at least half of the ones in my feed were of times my friends and colleagues had spent with him. Dinners, street encounters, book readings…for anyone who has worked in a restaurant, you could tell as soon as you heard him speak, he was one of us. And he showed us that what we did meant something, even if it was just a shitty brunch shift.

I was always disappointed to listen to interviews with Bourdain, because no one ever asked the right questions.

Even Fresh Air stooped so low as to ask him about eating unwashed warthog rectum, losing the purpose of why he ate it. He wasn’t there to eat that organ, he was there to learn about those people. It wasn’t Bizarre Foods — watch me eat this live scorpion. It was sitting at the tables of strangers to learn more about their lives, where they come from, and where they are going. He was a student of the world, and he shared with us what he learned.

He was a student of the world, and he shared with us what he learned.

I’d thought he’d always be around. I was looking forward to his last few seasons of the show before he’d retire to Vietnam, as he’d always said he wanted to do. I was looking forward to his next book, and hoping he’d pen another travel memoir, or maybe another graphic novel. Because right now in this world, we need his voice. We need his patience. Bourdain spent his career teaching us not to be scared of our neighbor, but instead to sit down with them and get to know them. To give them time and space to tell their stories. Or as he said…

“Maybe that’s enlightenment enough: to know that there is no final resting place of the mind; no moment of smug clarity. Perhaps wisdom… is realizing how small I am, and unwise, and how far I have yet to go.”