by Jessie Shires

Art by Corinne Pease

Jessie’s essay, “My Pleasure,” appears in The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour episode 3, which aired July 6, 2018.

My feet hurt. The ten-top that would have made up a large chunk of my income for the night no-showed. I haven’t had a bathroom break in six hours, never mind a bite to eat. Chef’s yelling at me for the modifications my guest requested. Table 14 left a pitifully small tip; the note on their receipt says my service was outstanding, but they didn’t like being seated next to the discreetly breastfeeding new mother. Table 29 is outraged that the plate she saw listed on a six-month-old menu online isn’t available this evening. We have ruined—RUINED—her birthday dinner. The gentleman seated at this same table earlier called me sweetheart and sugar and touched my hand way too much. My uniform still smells of his too-powerful cologne.

Did I mention my feet hurt?

Declining a refill on coffees, my last table asks for the check. “Thank you so much. We’ve had a wonderful time.” Their smiles are warm, their enthusiasm genuine.

I smile back: “It’s been my pleasure.”

And, though I’m still surprised every single time to realize it, the astonishing truth is this:

It truly has been.

The best servers I’ve known have a deeply conflicted relationship to their work. Despite the fact that it can be intellectually stimulating, physically demanding, and financially rewarding, restaurant work is not, as a rule, respected as a legitimate career choice. Most people who’ve never done it (even—no, especially—people who work IN a restaurant, but have never been a server) hold to the notion that it’s uncomplicated drivel. We jot down what people want to eat, bring a few things to the table, and that’s about it. You know: trained monkey stuff.

Despite the fact that it can be intellectually stimulating, physically demanding, and financially rewarding, restaurant work is not, as a rule, respected as a legitimate career choice.

The reality is humbling, and is the reason that so many industry veterans openly fantasize about subjecting all adults to mandatory employment in a service position—a draft to cultivate empathy, if you will. In a busy shift, you’re managing a running list of at least a dozen tasks, constantly shifting priorities, and the comically unpredictable expectations of a random collection of total strangers in various states of hungry, hangry, and intoxicated.

On other days, you will find yourself indentured into gross, bizarre, and tedious tasks—what job descriptions term “other duties as assigned.” You aren’t paid as a plumber or handyman, but you’ll be expected to play one on a slow shift. The pitfalls are many; some bigger than others.

For one, the power dynamic between customer and employee in our culture provides abundant opportunities for creeps, cheapskates, and bullies to get their kicks.

- I’ve watched an ostensibly-human being bring a 17-year-old host to tears over a simple wait to be seated on a busy night, gloating and grinning with every minute of it.

- I’ve witnessed adults eat an entire meal with relish, practically licking the plates clean, before demanding every last penny of it be comped because they “didn’t like it.”

- I’ve seen patrons wield Yelp, the restaurant owner’s name, and even baby Jesus himself as cudgels to get their way.

In each of these instances, all but the most heroic of managers rolls over, shows a soft belly, and gives the customer what they ask for—because you know who’s always right? It certainly couldn’t be the professionals who do this job day after day after day.

And, of course, there’s the tipping issue. This one’s been done to death, but experience tells me it somehow still bears repeating:

TIPPING IS AN AGREEMENT, NOT AN EXTRA.

When you take a table at a sit-down establishment in a locale where a living wage is not mandated for restaurant workers, you are accepting a temporary loan. The price of whatever you order is subsidized by the low, low wages the restaurant is allowed to pay its front of house staff (a hair above two bucks an hour for most servers). The bargain you make when you are seated is that you will enjoy the discounted menu prices AND help pay the staff directly, rather than pay what your meal actually costs while the owner pays a full wage.

It’s kooky, yes. There are many reasons to ditch this system—and, in fact, a growing number of restauranteurs are experimenting with various ways to do just that. But, for now, this is how it works. I understand that it’s uncomfortable to be expected to hand your money directly to another person, rather than leaving the business to handle payroll. Believe me; it’s equally uncomfortable to have to rely upon the goodwill, common sense, and math skills of your average citizen to earn a living.

Believe me; it’s equally uncomfortable to have to rely upon the goodwill, common sense, and math skills of your average citizen to earn a living.

Dissatisfied with your service? Fine. There’s a remedy for that.

Speak to the manager, and give the establishment the opportunity to make things right. Any place worth its salt wants you to be happy—and if they don’t, you should never go back there. A lower tip might very well be warranted, depending on the circumstances.

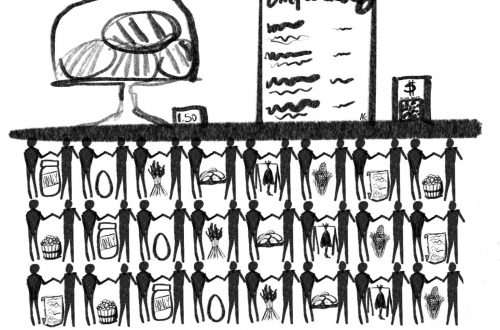

But remember: the server isn’t the only person relying on gratuities. Servers share a portion of every tip with the bartenders, bussers, backwaiters, and other support staff. So, while it may violate your sense of fairness to give a good tip to a less-than-stellar server, it’s almost always the right and moral thing to do.

Stiffing is the nuclear option, and that blast radius has more people in it than just the bumbling sap who got your order wrong.

Still not sure? Here’s a handy guide:

REASONS TO TIP 20%+

Almost every circumstance, period, end of story.

REASONS TO TIP LESS THAN 20%

Genuinely poor service. Note that this does not include circumstances outside the server’s control, such as (and I wish I were making these up):

- Unsatisfactory reservation or wait time, table location, or wine selection.

- An overly seasoned steak or an underly alcoholic cocktail.

- Outdoor patio seating was (surprise!) adversely affected by current weather conditions.

- Your preferred sporting event was not featured on the TV closest to your table.

REASONS TO LEAVE NO TIP

Practically none whatsoever. Unless maybe the server intentionally set you on fire, released a herd of diarrheac wolverines into the dining room during your meal, or finally snapped and took hostages before you got your dessert.

But back to the work.

After all this, somehow, we still love it. Fitzgerald pointed out: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

Sidestepping the question of intelligence rating, I will say that the best of us spend every day holding two diametrically opposed ideas in our hearts, each one hundred percent true:

We fucking hate this job. And we can’t think of anything else we’d rather be doing.

I used to be a Paramedic. I’ve seen a breathtaking array of death, dismemberment, profound psychosis, and garden-variety stupidity. From a front-line perspective, the parallels between food service and EMS are striking: in each, our responsibilities are complex and poorly understood by those outside the industry. You’re always managing multiple tasks at once, under conditions that are constantly changing. You must have the ability to inspire instant trust in strangers and correctly decipher their often-inscrutable needs.

Sure, a server’s mistake (apart from neglecting to document food allergies) isn’t likely to kill anyone.

But, having done both jobs, I can tell you that the skills and talents it takes to excel in one position are identical to what you need to succeed in the other. The real difference? As a Paramedic, I was on the receiving end of inspired and respectful attention from the public. As a server, I’m mostly asked when I’m going to get a real job.

But here’s the thing: a true professional, in any field, strives for excellence even when they have no reason to expect recognition or appreciation. You find this striving in the best doctors, scientists, and CEOs; you also find it in top-notch secretaries and garbage collectors and grocery clerks.

It’s what sets the finest humans apart, and it is its own reward.

This striving, and the satisfaction it brings, is what spurs so many of us on. Whether or not our work is respected, we are professionals. At least part of my day off will be spent studying menu items and preparation techniques, expanding my craft beverage knowledge, and keeping up to date on industry trends. I put in the work during my off time to make sure you have a stellar visit when I’m on the clock. So when I say it has been my pleasure to serve you, the words might seem like a meaningless platitude. But I’m using them to say thank you: thank you for giving me the opportunity to flex this muscle I’ve worked so hard to develop. I study the menu so I can answer your questions in detail and with confidence. I read about wine and go to tastings and attend classes so I can help you pick a bottle you’ll enjoy. I make sure I have the tools I need to do my job well, so that you feel effortlessly, elegantly welcomed when you sit at my table. And as with any job well done, the pleasure comes with the execution.

This striving, and the satisfaction it brings, is what spurs so many of us on. Whether or not our work is respected, we are professionals.

And so, even though my feet hurt and I’m exhausted and down to my last, frayed nerve; even though every single table has worn my spirit thin tonight with complicated dietary restrictions and outrageous demands and banal conversation, I’m being more honest than you can imagine when I thank you, and invite you to dine with us again soon. The pleasure, to my amazement, has indeed been all mine.

Artwork by Corinne Pease.