by Sofia Ferreira Santos

Sofia’s essay, “Rice,” appears in episode 17 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour, which aired on January 3, 2020.

Rice is a key part of many traditional meals in countries all over the world. Whether it’s used as a side for curries, or the main ingredient for rice pudding, most of the world’s cultures swear by it. In Brazil in particular, rice is the main food that we consume, with our traditional meal being made up of rice, beans, and beef.

It’s so endearing to look back at childhood when my parents or grandparents would shout out “olha a janta!” and I’d have to come back into the house from an afternoon of playing with my neighbourhood friends, to eat dinner as quickly as possible so I could go back outside again. I’m definitely not the only one with this sort of nostalgia, nor the only Brazilian who tried to scoff down their rice and beans in five minutes or less so they could go back to playing or riding their bikes.

There’s a specific way of cooking it as well – at least in my family’s house – that made rice even more special, and almost a ritual. You’d always have to chop your onions, crush your garlic, dice some potatoes and carrots, use a cup to measure out your rice and wash it until the water ran clear, fry it on some oil and leave it boiling in 3 fingers of water with the lid on and leave it alone.

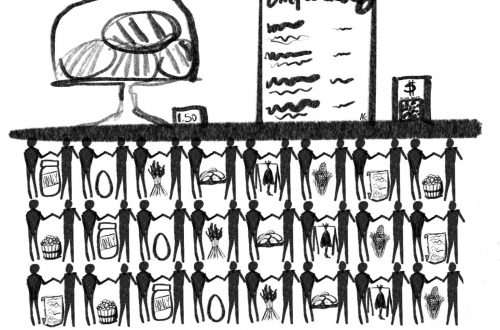

Rice is an item which we don’t give too much thought to, but that connects us all as a people. Don’t get me wrong, Brazil is a very divided country and it will most likely remain that way for a very long time. But things like rice and beans are a huge part of our general culture, and it’s hard to find a single person, whether white, black, rich or poor that doesn’t incorporate it into their diet in one way or another.

Rice is an item which we don’t give too much thought to, but that connects us all as a people.

Its history, however, is a curious one, and a story which lives with a small minority of the population. Most people don’t really question where or how exactly rice came to Brazil and became such a staple – after all, it’s just another food item that we purchase without giving a second thought to.

But its hidden history tells how rice made its trajectory to Brazil in a sacred way which reflects our history, culture and ancestry. As with many things – including the Americas – the existence of rice in South American countries is usually awarded to white colonials who supposedly traveled with the grain from Asia and planted it in our land. With little written sources to back up any other alternative, it’s easy to see how this is the widely believed narrative.

Yet, there is a version of the story which subverts this narrative, and provides an alternative which makes sense to many of us. Many Brazilians, especially those of us with deep roots in North Eastern, mainly-black states like Bahia, have heard stories passed on throughout generations about how rice was really brought into Brazil. The oral tradition, passed on from family member to family member, tells the story of how African women who were enslaved and brought to Brazil were robbed of their cultures and traditions and stripped of all they knew during enslavement, and had to find another way to allow their cultures to survive. The brutality of slavery had many fearing for their lives and the lives of their families even before being taken across the Middle Passage.

Some enslaved women realized that the only way for their future generations and cultures to survive was to ensure that they were orally passing on their histories and cultures to future generations. Many of their cultures favoured oral traditions rather than written, as well as many of their successors born into slavery would never be taught how to write – so creating oral narratives and songs to share their history became the chosen mode of cultural transferral. Most strikingly, though, many enslaved women took it upon themselves to save their traditions, including those based around food, hiding grains and seeds in necklaces and bracelets, and hiding grains of rice in their hair throughout their trips from Africa to the Americas. The story tells that once on South American shores, these women hid and planted the grains and seeds, without their Masters’ knowledge, to ensure their children would always be able to eat.

Most strikingly, though, many enslaved women took it upon themselves to save their traditions, including those based around food, hiding grains and seeds in necklaces and bracelets, and hiding grains of rice in their hair throughout their trips from Africa to the Americas.

In quilombos, both during slavery where they were used as hideouts and communities of runaway slaves, and in today’s quilombos, rice is often still cultivated in this way, and remains one of the most important food items. As many quilombo residents come from a long line of ancestry leading back to the enslaved people who originally established the community, it’s hard to question that many of the habits, cultures and traditions still alive today could easily be traced back to the founders of the quilombos too.

The colonial narrative, which claims grains like rice and other foodstuffs like cassava were brought from Asian countries, is solely based on travel journals and personal diaries kept by slave owners and colonials during their expeditions – yet they somehow still hold a lot more grund with Western academics and overpowers the social memory of thousands, if not millions of people. In a way, this debate is almost one person’s narrative against a whole group’s: but due to the freedom status and skin colour of the opponents, somehow the one person narrative has won every time.

In parts of Brazil, this oral tradition is still passed on through generations, and many women still adapt the same cultivation methods as their enslaved ancestors did back then. Using a pilão (a wooden pestle and mortar), many North Eastern Brazilians still cultivate rice in the same way, using the pilão to break up its grains. Not only that, but African cultivation tools like the pilão were adapted into other parts of our food culture, being used to make butter, peanut pé de moleque and the traditional paçoca – which my granny always makes on her pilão in Bahia!

There are also specific rice varieties, such as the red rice, that never had its roots in Asian countries, but can be traced back to Africa – and though colonials tried to take ownership of bringing these grains over, there’s no logistical way they could’ve done so. Academic Judith Carney exposed this theory to the Western world in her revolutionary research piece ‘With grains in her hair’, or the ‘black rice thesis’, and was met with a lot of controversy and claims that oral traditions isn’t sufficient evidence. And though Carney’s research was groundbreaking for Western audiences, it just confirmed what many of us who have heard these stories since childhood have known, and gave us a written source to claim back our food history with.

Custom illustration by Corinne Pease

Sofia Ferreira Santos

Sofia Ferreira Santos is a Brazilian freelance journalist and content creator based in East London. You can always find her in front of a computer writing about Brazilian politics and culture or talking about race on Instagram. See Sofia’s work on her website.