by Greg Higgins

Greg’s essay appears in episode 22 of The Dirty Spoon Radio Hour.

It’s hard to say when it first started, sometime around Valentine’s Day many years ago. I’ve been committed to it ever since. The ritual commences with the thorough vacuuming of a simple sheet of plywood laid over my basement workbench, my “grow room.”

I had become tired of the sleuthing for healthy interesting vegetable starts at local nurseries and plant stands. Nearly always the same handful of varieties and plants that were often neglected or just not ready to make a vigorous go of it when transplanted in the ground. At first it was a modest endeavor, a handful of chili and tomato seed packets with exotic names from pondered catalogs that would be sown and nurtured on that board. It’s a labor of commitment, no wavering allowed, sound seeding techniques and diligent watering and feeding. The rewards are in the act of care, the sense of bonding as each small grain of seed awakens and comes to life.

Gradually, as the number of alluring seed choices grew, it became harder and harder to resist the intrigue of the new and the rare. Bhut Jolokia, Aji Limón, Lai’s Thai, Ananas Noir, Trinidad Scorpion, Lucky Tiger, and many others joined my annual family gathering. Each with their own history and lore. Ethnobotany is the story of plants and people, and each of these unique nightshades had an engaging yarn to share. Some arrived in the mail, but others came from friends with stories of people and places where they had been passed on year after year in the ancient tradition of seed saving. These became some of my favorites.

Ethnobotany is the story of plants and people, and each of these unique nightshades had an engaging yarn to share.

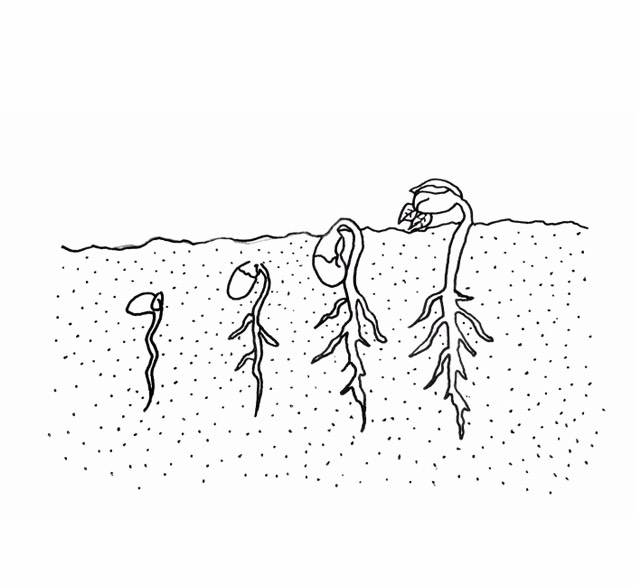

Many of these heirloom chilies are subtropicals; varieties hailing from Central America and the Caribbean, far warmer lands than our own cool temperate maritime climate. They require long days, lots of warmth and an extended growing season. From their sowing in mid February, many of these seedlings will require 120 to 150 days to maturation. That hopefully means a harvest in August or September with some favorable summer weather. To have success and bring them to fruition in this place entails some thoughtful gardening and well controlled conditions. Preparation of the cell trays begins with some good soil, moistened and evenly dispersed without compaction in the trays. Two tiny seeds are sown per cell and then topped with a fine covering of sifted peat moss. It’s like many tasks, very simple in nature but in need of precise execution. A system of careful labeling is key here, too; someone hoping for a sweet luscious Lesya pepper might not see the humor in the feisty fireball of a Fatalii chili.

As I sow these magic grains, my mind wanders to my expectations for their eventual harvest and what they’ll become in our home kitchen or at the restaurant. Some will find a place on a charred, bubbly crusted cheese laden pizza from the wood burning oven in the backyard. Others, the super hot and spicy types, will be slowly fermented into a tangy piquant chili sauce and preserved for use throughout the year as a cornerstone seasoning of our preparations at the restaurant.

The sheer numbers of these cherished green children have steadily grown over the years. Like my love of cookbooks, I have never really been able to pass up an opportunity to acquire a new heirloom seed variety. Because of this fact, some years ago I moved up to a 128 cell tray system. Initially that seemed adequate, but of course I doubled that the following year. Yes, 256 robust little tomato, chili and eggplant starts seemed the perfect amount. Really there was no choice, as once transplanted into three inch pots, it yielded ten full plant flats which completely engulfed my little room with a sea of green.

The ritual expands as do the plants; their first leaves open and the seedlings express their needs on a nearly daily basis.

The ritual expands as do the plants; their first leaves open and the seedlings express their needs on a nearly daily basis. To produce healthy, vigorous vegetable starts, the plants need to experience optimal growing conditions and periods of discretely applied stress. Water, wind and nutrients must be offered to yield the desired healthy results. While responding to all of this there’s lots of time to think. How many of these offspring can we plant in our garden? Out of all this abundance how does one choose those that will stay to fill our raised beds and troughs? The hard truth is that really only about three dozen of them will make that short journey. The others will go out to homes elsewhere and other friendly gardeners.

It’s an enriching experience to share a living thing that holds so much promise. As the number of varieties and starts grew each year, so did the number of friends, neighbors and acquaintances who were to receive them. Seeds are cheap and the act of growing knows no price, it’s a selfless Zen-like exercise. Whether to Biz, our mailman; Lai who cuts my hair; cooks and servers at the restaurant; customers and passersby; or to the so many others that will be tasked with taking part in this magical rite.

As I choose those that we’ll plant and then begin to adopt out their siblings, a sense of completion comes over me.

So, what started out as a sensible hobby has taken on a life of its own. Not unlike Johnny Appleseed, our annual nightshade festival has become a catalyst for positive social engagement. It sparks conversations of gardening, cooking, people, places and cultures. As I choose those that we’ll plant and then begin to adopt out their siblings, a sense of completion comes over me. By early June the grow room will be nearly empty and I feel a touch of melancholy over the plants’ departures. Soon, however, a new cycle begins in the open air. Those tiny starts begin to grow and flourish, maturing into lush specimens of their kind. Flower buds develop and open and fruit begins to set and ripen as the season advances. We are richly rewarded by this cycle of expectation and optimism and the harvest of satisfaction it yields.

Custom artwork by Corinne Pease.

About Greg Higgins

Greg Higgins is a prominent figure in the development of Northwest cuisine and a national voice for sustainable dining. He opened his restaurant, Higgins, in Portland, Oregon in 1994 with co-owner Paul Mallory. Higgins uses his close ties to Pacific Northwest purveyors to spearhead his pioneering menus and showcase the bounty of the Pacific Northwest. In 2002, Higgins was chosen Best Northwest Chef by the James Beard Foundation, and in 2005 his restaurant was selected by Nation’s Restaurant News for the Fine Dining Hall of Fame. He is a founding member of the Portland chapter of Chefs Collaborative, a national organization whose goal is to promote sustainable cuisine by celebrating the joys of local, seasonal, and artisanal cooking.

photo by John Valls